Sovereign wealth funds are becoming more transparent and upping in-house management – but they remain elusive for many IR teams

When Visa was on the runway for its IPO in early 2008, the bankers running the deal suggested meeting with sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) in the Middle East where they detected substantial interest. But they advised the global credit card giant to follow a two-step process ‘to bridge any cultural divides,’ recalls Jack Carsky, senior vice president of global IR at the credit payments company.

‘We made the effort to go out on two separate occasions’ to make initial introductions before the funds would get serious about investing, he recounts. The meetings ‘looked like the UN’, with the lead analyst ‘a kid who grew up in Iowa’ joined by colleagues from China and India. ‘The common factor was they were all fantastic analysts.’ The extra effort paid off when SWFs ‘became a cornerstone’ in the IPO, Carsky states.

SWFs remain a part of Visa’s IR program, but Carsky for the most part relies on the sell side to reach out and target new funds or keep in touch with existing ones. ‘That’s where the relationship lies,’ he explains. SWFs are ‘pretty much hands-off. If they want to see you, they’ll let you know.’

In a recent white paper on SWFs, the market intelligence firm Ipreo observes that SWF assets are ‘some of the largest pools of capital on the planet.’ But the paper cites a familiar litany of concerns: most funds have little face-to-face contact with current or potential portfolio firms, several use outside managers, and disclosing portfolio positions ‘is the exception rather than the norm’. With a reputation for secrecy and opaque investment policies, SWFs have typically been viewed with skepticism by IROs and CFOs in developing IR strategy and targeting programs.

Big issues

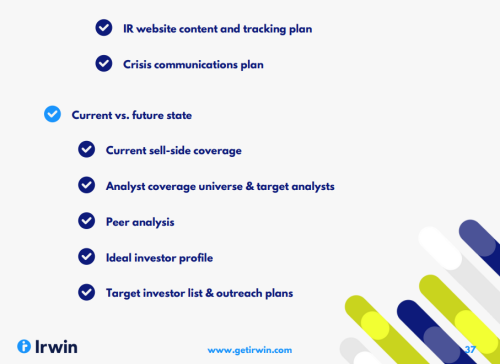

Even so, SWFs are too big to ignore – and they’re changing. Over the past few years, several funds have increased transparency, taken more management in-house and added professional buy-side talent. Savvy IROs need to familiarize themselves with this species of investor in case they come knocking at the door – which today is still the typical way an IRO would meet one. As a result, the best and easiest way for IROs to target SWFs may be through the sell side and active external managers.

Michael Maduell, CEO and co-founder of the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, believes IROs should ‘have a keen interest’ in SWFs for several reasons, including as potential strategic shareholders, sources of what he terms ‘patient capital’ and as a component of a CFO’s corporate capital structure thinking. Their investment flexibility means SWFs can participate in all manner of structured investments beyond pure equity, from private investment in public equity and corporate debt to private equity. ‘They even invest in Chicago parking meters,’ Maduell says.

Since the launch of the first SWF, the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), in 1953, the basic rationale has been the same: to manage assets resulting from the balance of trade surpluses to the benefit of the domestic government. It wasn’t until the 1970s – when Singapore, Abu Dhabi and Canada all created their first SWFs – that the notion of an SWF began to take hold. In 1990 it was estimated that SWFs controlled about $500 bn.

As commodity prices shot up over the past decade there has been an explosion of funds, with more than 30 established since 2005, while assets under management grew nearly 60 percent between 2005 and 2012. Today, more than 80 funds control nearly $6.4 tn in assets, three quarters of which is held by the top 10 funds, according to the SWF Institute.

Most SWFs have built their assets on petroleum exports, the largest being the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global (NGPFG). But not all funds are commodity-based: five of the top 10 funds manage trade surpluses for the Chinese and Singaporean governments (see Top 10 sovereign wealth funds, below). And SWFs are found on every continent, with most of the largest funds concentrated in the Middle East and Asia.

While their reputation for opacity regarding portfolio holdings, investment policy and governance was historically deserved, that reality is changing, argues Maduell. Funds located outside the US have typically avoided disclosing their holdings in US firms, either using an intermediary manager or falling outside the 13F disclosure filing requirement, but a few have started to voluntarily disclose some holdings.

Motives are sometimes called into question as well. When China National Offshore Oil Corp tried to buy the US oil refiner Unocal in 2005, the effort blew apart when US politicians and commentators raised national security concerns.

Maduell and Carl Linaburg, co-founder of the SWF Institute, realized SWFs suffered more than a credibility gap – there was also an information gap. In 2007 they launched the Linaburg-Maduell Transparency Index. Without making any judgments about content, it scores SWFs based on how open, comprehensive and accessible their disclosure practices are. The International Monetary Fund and a group of SWFs followed suit in 2008 with the Santiago Principles, a voluntary set of best practices for fund administration and operation, calling for disclosure of policy objectives, governance structures and fund statistics.

Maduell credits the Transparency Index and the Santiago Principles with increasing SWFs’ communication with stakeholders. When he and Linaburg launched the index, most funds did not have a website or even provide a phone number, a situation dramatically different from today.

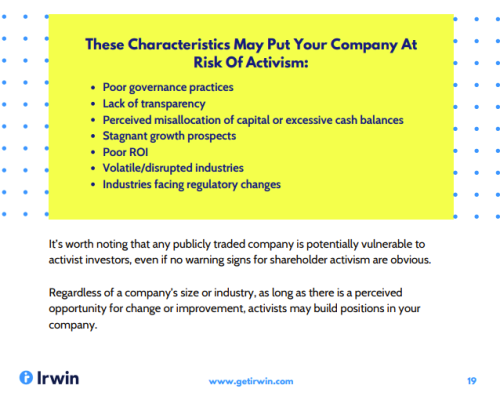

The Norwegian SWF is among a handful of funds that earn a perfect 10 on the index. NGPFG ‘tries to publish everything,’ says Maduell. It discloses portfolio holdings, issues press releases on developments within the fund and posts white papers about its activist approach to governance issues, particularly around ethical investing and sustainability. But NGPFG stands out as unusual: most SWFs are either passive on governance issues or their governance policies are not disclosed, Maduell notes. SWFs can and do invest in private equity, but historically have not been activist investors or sought board seats directly, he adds.

Supporting role

SWFs’ negative reputation began to soften during the global financial market meltdown in 2008 when several funds behaved just as they had been designed to do. Though SWF architects probably never contemplated the extreme circumstances they found themselves in, the funds helped stabilize their home markets by propping up domestic banks. Several (most notably Singapore) also took positions in liquidity-starved US and European banks.

A study of SWF asset management trends by Invesco finds the Arab Spring has shifted many funds’ objectives from financial investment to domestic development and infrastructure. While this may limit or slow the growth of investment in equities, it also increases the pressure for SWF transparency. SWFs have become ‘very self-conscious’ as citizens have asked ‘where their public treasure is going,’ Maduell explains.

While he sees SWFs as an attractive investor class overall, Maduell highlights the importance of IROs tracking SWF ownership. A fund from a country with an anti-democratic reputation taking a stake in a company with national security connections ‘will probably make CNN news headlines,’ he says. For example, during the Libyan uprising the Libyan Investment Authority’s 3 percent stake in Pearson, owner of the Financial Times, was frozen by order of the UK government, he recalls.

Brian McMahon, director of investor targeting for NASDAQ OMX, says SWFs are ‘growing in influence’ for IR programs. With a presence in New York, London and Hong Kong, the larger SWFs make themselves accessible to firms near the fund’s home turf and some attend major conferences or visit company offices. McMahon is also seeing more SWFs managing equity portfolios directly as opposed to allocating them to sub-advisers or index funds, and he sees several funds adding experienced buy-side managers to their teams.

The increased professionalism shows: clients report that fund managers ‘tend to do their research before they reach out to a firm’ and come to meetings well prepared, McMahon adds. Even so, SWFs ‘do not make sense for everyone,’ he cautions, as many lean toward large and mega-cap stocks, expect C-level interaction, and ‘rarely oblige IR-only meetings’.

Yet there are still opportunities for IROs to reach out to SWFs, according to Sudarshan Setlur, director of global markets intelligence at Ipreo. Some smaller funds that can’t command a CEO appearance welcome the chance to meet with a knowledgeable IRO, he says. He also sees some funds becoming more proactive and taking meetings on non-deal roadshows, something he ‘never’ saw three or four years ago.

Fund snapshotsTargeting tips from Ipreo’s sovereign wealth fund white paper:Norges Bank (manager of Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global) ‘Easily the most open and likely to communicate with issuers... strong advocate of good corporate governance practices… such as board independence and sustainable practices.’ Abu Dhabi Investment Authority ‘Tends to be somewhat less transparent… Abu Dhabi favors technology and financial… consumer services and industrial companies… heavily invested in North America and Asia… has a London-based presence.’ China Investment Corporation and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) Investment Company ‘Historically secretive, [both] have improved their disclosure policies significantly in recent years, although a large portion of their investments remains a mystery… (SAFE is) opening an office in New York to handle investments in real estate and other US assets.’ Kuwait Investment Authority ‘Does not publicly disclose many holdings despite frequently meeting with issuers… UK office in particular often meets with management of both US and European companies… increasing investment in infrastructure and real estate.’ Government of Singapore and Temasek Holdings ‘Offices in New York and London where issuers frequently meet with analysts and portfolio managers… fairly diverse, though financials, technology and consumer goods companies are held most widely... heavily invested in Asian financial firms.’ |

*Estimated. Data correct as at February 2014. Source: Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. Click for a larger image