How are companies coping with either too much or too little sell-side coverage?

Restructurings, downsizings, mergers, scandals, mega-fines, sensational trials and bankruptcies have scrambled both the corporate and player rosters among some of the biggest sell-side names. So where are we now? A successful sell-side franchise has always been built on product, service and distribution.

Bringing in new management can help attract coverage – Fiona Tooley, TooleyStreet Communications |

Today, however, the integrity of the research product has come under fire, corporate management access has become the mainstay service offering, and transformed markets have created more tailored and client-specific distribution options – all further straining the traditional sell side.

Despite these pressures, larger companies have watched as ever-more analysts pick up their stock, attracted by the lure of high trading volumes and a slice of the commissions on offer. One potential issue – albeit a rather luxurious one – is how to manage all that attention. On the other hand, sometimes just securing any analyst coverage can be a challenge. The strain on the sell-side model has made it harder for smaller companies – with less commission-generating potential – to get noticed.

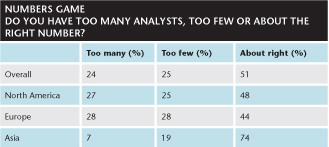

IR Magazine’s latest research on dealing with the sell side – found at the center of this magazine – points out that roughly a quarter of companies globally believe they have too many analysts, and a quarter believe they have too few (see Sell-side analyst coverage). Breaking down the results by geographical region, these findings hold true in Europe and North America, although Asian firms show less concern about large analyst numbers, with only 7 percent of respondents noting an overabundance.

Over the next four pages, we analyze the problem from both angles: how are companies coping with having, in their opinion, too many followers? And what success stories can be shared in the struggle for attention?

The many

‘Having too many analysts covering your company is a high-class problem these days,’ observes Dennis Walsh, vice president at Boston-based IR consultants Sharon Merrill Associates. Nevertheless, even a high-class problem is still a problem.

As IR Magazine’s research shows, nearly half of mega-cap companies and three out of 10 large-cap companies globally raise their hand when asked whether they have too many analysts. And it’s not just market cap size that can generate over-coverage; a hot sector can also attract an outsized following, even for small-cap companies. Tech, media, consumer, energy and healthcare companies of all sizes complain of an overabundance of analysts.

Sometimes a flood of analyst attention can come unexpectedly, and for reasons outside the company’s control or view. Former Keefe Bruyette & Woods regional bank analyst Timur Braziler describes how M&A activity in the banking sector dried up after the market meltdown and great recession beginning in 2008.

As a result, Braziler, who is now a vice president of investor relations at research firm Corbin Perception, says the major bulge-bracket firms started moving their research effort downstream to smaller banks they would never previously have looked at, positioning themselves for corporate finance work down the road.

Source: Sell-side analyst coverage, July 2013

More is sometimes less

While their situations may not generate much sympathy from IROs struggling to attract sell-side coverage, the problems arising from too many analysts are still real. Some complaints about the sell side are universal, however many analysts follow a company.

For example, the analyst who repeats rumors and speculation to drive trading or repeatedly tries to go around the IR professional can be particularly troublesome. Then there are the ‘lazy’ analysts who regurgitate company news, adding no original thought, and others who never call but regularly issue ill-informed research and out-of-date earnings models.

The familiar failings of the sell side can play themselves out differently when a company suffers from an overabundance of analysts, however. And unique challenges are presented by the very fact that crowds of competitive analysts are elbowing one another to win recognition in the marketplace and build relationships with company senior management.

For example, consider the flood of conflicting – or just plain overwhelming – requests for executives’ time that a flock of competing analysts can demand. An IRO navigating those cross-currents while trying to preserve valued long-term relationships – and his or her own sanity – needs the skills of a negotiator, diplomat, auctioneer, confidant and occasional disciplinarian.

‘We can’t do an annual event with each analyst because there are so many,’ comments one mid-cap research respondent.

IROs also highlight the diminishing returns from dealing with a large number of followers. ‘I’m not sure how many opinions can be had on any one company, but there just can’t be 27 different views,’ comments a survey respondent. ‘It creates a lot of work for IR without necessarily creating any value for investors.’

Kris Wenker, IRO at mega-cap food giant General Mills, observes that of the 20 analysts submitting estimates on her company to First Call, there are a handful that merely go through the motions. ‘I see no evidence of an active effort (by those analysts) to monitor company performance or to publish substantive analysis or research,’ she reports.

Even so, she sees real value in nurturing the large sell-side following General Mills enjoys. With the stock viewed as a core position in many portfolios, Wenker realizes that published research can not only broadcast the investment case more widely than she could herself, but also help a ‘very stretched’ buy side stay ‘up to speed’ with General Mills’ strategies and results.

Wenker does not discourage additional coverage nor does she have any specific target for the amount of coverage. ‘As with so many things, it’s not the quantity that counts – it’s the quality,’ she explains. ‘And we are fortunate to have some long-tenured, knowledgeable sell-siders covering us.’

Don’t burn bridges

Walsh observes that there is no optimal number of analysts and advises clients to continually foster new relationships with non-covering banks ‘because you never know when an existing analyst will leave his or her company or decide to drop coverage on your firm.’

A more diverse following would be more useful than a higher number of analysts – Juha Laine, Metsä Group |

Even a relatively large analyst following does not guarantee the right kind of coverage; on the contrary, it may crowd out more desirable analysts. Juha Laine, IRO at Finnish packaging and paper manufacturer Metsä Group, currently counts 14 analysts who follow the company but would prefer a different mix, both geographically and by industry focus. ‘Some good London-based analysts would probably help,’ he says. ‘We’d like to be compared more with packaging firms and have packaging company multiples.’

Cole Lannum, IRO at healthcare company Covidien, sees one direct benefit from having a couple of dozen analysts following the company. ‘The mathematics of large numbers tends to work in our favor,’ he says. ‘The more data points one has, the less impact any one data point has on the overall consensus.’ Beyond that, he remains philosophical about trying to manage outliers. ‘The analyst owns his or her opinions and if those opinions differ from our stated strategy or guidance, then so be it,’ he concludes.

The few

In a scenario familiar to any IRO with a meager sell-side following, the long-sought introductory meeting has gone well. Your story resonates, your CFO has handled all the questions and the portfolio manager definitely seems interested. Then, almost as if by script, he or she leans across the table and asks: ‘Why the lack of coverage?’

‘It’s a question that requires an answer,’ says Leslie Kratcoski, IRO at tools and equipment manufacturer and distributor Snap-on. She believes many portfolio managers see coverage as a sign the firm has been vetted, concluding that more coverage lowers the risk of surprises. But any explanation for lack of coverage can be as complicated as the question is simple.

The challenge of declining commissions is often cited as the major driver for shrinking analyst coverage, particularly among small and mid-caps. And, as the latest IR Magazine research shows, coverage follows cap size. Nearly six out of 10 small-cap firms report inadequate sell-side coverage, while no mega-cap feels underfollowed. But there are always company-specific issues, too, as even some small caps report too many analysts while some large caps feel underfollowed.

No matter how problematic the sell side can be, the trade-off between too few and too many analysts is an easy calculation for most IROs; the harder calculation is figuring out how to attract more coverage. Poor financial results, a muddled strategy, uncommunicative executives, a small and stretched management team simply unwilling to invest time in IR activity, major strategic repositioning, a complex set of unrelated businesses or a unique niche with no easy benchmarks – any one of those conditions can give pause to an analyst thinking of adding a name to his or her coverage universe. Two or more factors in combination will likely be fatal.

Change for the better

Attracting the sell side into a stock can sometimes be as ‘simple’ as bringing in a new leadership with a respected track record and existing relationships with investors. Fiona Tooley, IR consultant and founder of UK-based TooleyStreet Communications, recalls that situation played out at a client, Trifast, a global contract manufacturing and logistics company.

‘A few more analysts would be helpful, but I’m not sure 10 more would be’ – Leslie Kratcoski, Snap-on |

After Trifast struggled financially for years, analysts’ confidence in management waned and the company lost all sell-side coverage in 2007. Two years later, a former – and well respected – CEO returned as chairman of a reconstituted board to begin a major turnaround. Analysts revived coverage, based on ‘the trust and respect’ they gave top management, Tooley says. Even during the two-year hiatus, Trifast retained a firm to provide company-sponsored research, which provided an important information source to investors and laid a foundation for the return of traditional sell-side coverage, she adds.

For most companies, however, the solution is more complex than bringing in a new chairman and may include a combination of proactive (some might say aggressive) outreach, accessibility, educating analysts – and timing. Any company reinventing itself through strategic repositioning, acquisitions, divestitures or restructurings invites a ‘show me’ response from analysts and investors. ‘It really is challenging to get the investment community focused on a segment that is 10 percent of your business,’ observes Braziler. They will be deaf to assertions the company is changing ‘until you show results,’ he argues.

Another crucial piece of the puzzle is understanding each firm’s business model and analysts’ compensation structure. ‘The company’s profile must reflect revenue opportunity for the sell-side name,’ observes Patty Bruner, managing director at Christensen, a global IR consultancy. She cites small cap size, modest trading volume, lack of volatility, moderate growth, no corporate finance needs and limited investor interest, any one of which could ‘lower revenue opportunity’ and deter sell-side interest.

Even if an analyst finds limited revenue in covering a particular firm, a case for coverage can still be made. Walsh advises clients to give a targeted analyst ‘a compelling reason’ to pick up coverage. ‘Make the case that covering your company will help the analyst to better understand the market drivers that affect the larger businesses he or she covers,’ he says.

He also urges undercovered firms to be aggressive, mounting their own company-sponsored non-deal roadshows ‘at least once a quarter’ and soliciting invitations from non-covering analysts to present at their conferences, both to build relationships with target analysts and to demonstrate interest in the company among the analyst’s buy-side clients.

More difficult is the ‘vicious cycle’ Walsh says low trading volume creates. ‘The buy side avoids low-volume stocks because it cannot easily get out [of them] and the sell side isn’t interested’ because of low trading commissions, he explains.

The sell side is also searching for new approaches that may hold hope for the underfollowed, including the rise of independent and boutique research houses. Micro and small-cap companies in particular should target boutique firms, Walsh adds. ‘Some of those firms seek undercovered stocks and prefer to initiate,’ he says.

Finally, as Kratcoski observes, there is ‘a point of diminishing returns’ in adding analyst coverage. ‘A few more analysts would be helpful,’ she says. ‘But I’m not sure 10 more would be.’

Teamwork and auctioning management timeWith 22 analysts following the $31 bn market cap healthcare company Covidien, IRO Cole Lannum says responding quickly to analyst questions and equally distributing management access are his biggest challenges. His solution is a combination of a team approach and an innovative ‘bid-ask’ auction for management time.Asserting that ‘responsiveness is always our number one priority,’ Lannum says no single person on his team is assigned to the sell side. Instead, responsibility is shared among Lannum, his number two Todd Carpenter, and executive assistant Ann Broughton. To allocate marketing requests among the cadre of healthcare analysts, Covidien developed a simple ‘reverse bidding’ auction system. ‘Each analyst receives a limited set number of bid points, and they bid on the importance of each event,’ with the highest bid usually winning, he explains. Covidien tries to award at least one event per firm every single year and rarely does ad hoc meeting requests. |

No snap answers to increase coverageWhen Leslie Kratcoski joined Wisconsin-based Snap-on in 2010 as IRO, she stepped into a role that had been vacant for three years as the company repositioned its businesses. During that hiatus, sell-side coverage fell, as much by neglect as anything, Kratcoski reflects.As a result, she had only three analysts actively following the S&P 500 firm when she joined. Today she has managed to double that number through a combination of proactive outreach, accessibility to other analysts (the company participated in 12 conferences last year) and basic blocking and tackling. Given its complex mix of businesses and no readily comparable benchmarks, Snap-on is not an easy company to follow. The traditional tools business that built the Snap-on name over the past 80 years has been augmented by diagnostic software, services and – most recently – a financing arm acquired in 2009. Industrial sector analysts are not used to seeing a mid-cap with a wholly owned captive credit company, Kratcoski says; it adds ‘a level of complexity’ that can be intimidating. To counter this, she provides detailed supplemental information so analysts can value each part of the business separately. |