The current economic state is making it difficult for companies to forecast sales, revenue and earnings. Advisers have pointed to broader forecasting weaknesses

Few things are more irritating to an investor than making a decision based on guidance that turns out to be rubbish. A recent study suggests that a majority of corporations may be trashing their reputations with forecasts (and, as a result, guidance) that could be considered more akin to throwing darts at a board than proper mathematical modeling. IR, of course, is left to pick up the pieces.

In a study of internal forecasting completed in late 2007, management consulting firm the Hackett Group found that two out of every three companies are unable to accurately forecast earnings one quarter in advance, missing the mark by anywhere from 6 percent to over 30 percent.

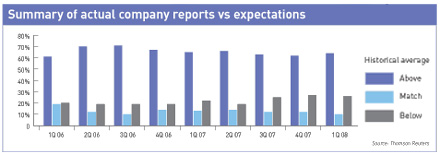

Companies are also weak when forecasting sales. More than half of the companies in the study of 70 large US and European businesses were unable to accurately forecast sales for the next quarter. Accurate forecasts, for the Hackett study, are defined as being within 5 percent of actual results. Additionally, Thomson Reuters’ survey research of S&P 500 companies shows that, historically, results match forecasts only 19 percent of the time.

There are competing explanations. Companies themselves are blaming the slumping economy, saying there is too little visibility. Starbucks, JCPenney and CVS Caremark are among a range of businesses that have announced this year that they will stop providing either monthly sales figures or annual profit information.

Hackett, a London and Atlanta-based firm, says rapid fluctuations in commodity and energy prices have simply exposed endemic weaknesses in the modeling methods most companies have been using. ‘A lot of companies have just been going through the motions for many years,’ says Hackett finance advisory practice leader Bryan Hall.

Although management teams are aware of the new economic conditions, they haven’t revisited and adapted their internal processes. ‘You ask companies why they forecast this way, and the answer is that this is the way they’ve always done it,’ says Hall. ‘In the past, they were just never exposed to the risk that highlighted how bad the process was.’

Unfortunately for IROs, guidance can only be as accurate as internal forecasts. Investors and analysts often have little patience with inaccuracies, and errors can rapidly lead to a loss of confidence. ‘Once you give guidance, you’ve set the expectations,’ says David Waldman, president of New York-based IR consulting firm Crescendo Communications. ‘You miss once, and people can get past it. You miss twice, and it really compromises your credibility.’

Some industries that have not historically been sensitive to factors like commodity prices, and so have not built them into their forecasting models, have suddenly found themselves in the economic crosshairs. ‘If you look at casinos, they’re either drive-in or fly-in,’ says James Lee, president of Lee Strategy Group, who represents a Native American casino. ‘Fuel prices have a tremendous impact on the people going there.’

The late show

In addition to the general forecasting problems most companies have during times of rapid economic change, some industries are particularly susceptible to error. Erik Randerson, currently vice president of IR at consumer internet media company United Online, used to work in the telecommunications equipment and software industries, where buyers hold out until the very end of a quarter in an attempt to leverage the pressure to make targets as a tool to negotiate better pricing.

‘What you find is companies like the one I worked at several years ago would do 30 percent or 40 percent of their sales in the last few days of the quarter, so it was difficult to predict results,’ he says.

The banking industry has quite recently had acute problems with forecasting, though for entirely different reasons. According to Mark Collinson, a partner at CCG Investor Relations in Los Angeles and a former banker, the banks do understand issues of risk, ‘but they have too many incentives internally to take risks rather than manage them.’

All these factors, as well as increasing demands from investors, complicate the IR role. ‘The psychology of guidance right now is so different from seven or eight years ago,’ Lee says. ‘It’s becoming much more of a moving target to try to figure out what to do.’

Back in the 1990s, a common approach was to use the ‘Scotty effect’, as Lee puts it. Scotty was the

engineer in the original Star Trek series. Whenever asked for something in a crisis, he would pronounce it impossible, and then find a way to deliver. Investors in this period often enjoyed happy surprises. ‘It added to the almost euphoric climate of the times,’ Lee says.

Future perfect

Today such events are rare, and investors prefer accuracy. ‘You get punished because people assume you don’t know your business,’ Lee explains. ‘You’ve got to be dead on. Apple reported record earnings, but they were under its estimates by 2 cents a share, and the stock went down. There’s a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t environment for many firms.’

What is best, agree a number of IR practitioners, is to provide guidance with enough background and explanation of the risk factors that are outside the control, or even forecasting ability, of the company.

‘If you continue to miss guidance, it is clear that some kind of process in your organization is going wrong that you should be able to control, but can’t,’ Collinson says. ‘I think investors initially understand about unknowable risk, however. It’s not a surprise if the CEO stands up and says, Our forecasts were wrong, and here’s why.’

This means a company must know, in advance, where problems could arise and why, which brings everything back to forecasting processes. An IR staffer may have to go back to the CEO and explain the options: examine and improve the forecasting process, so guidance accuracy can also improve, or be perceived as being out of touch with the business and watch the stock take a hit.

Put that way, investing some resources into improved forecasting doesn’t seem like such a burden after all.