Proxy access and say on pay covered, while ‘pay-parity’ disclosure could prove problematic for companies

‘The making of laws is like the making of sausages: the less you know about the process, the more you respect the results.’ The politician who said this sure knew what he was talking about – despite lawmakers’ lofty promises to exact revenge on the forces that brought the economy to its proverbial knees, the crusade to overhaul the financial regulatory system has been pockmarked by partisan mudslinging, horse-trade politicking and aggressive lobbying.

The 2,316-page mountain of legislative sausage – which funnily enough includes an amendment to the Paperwork Reduction Act – is something of a mish-mash of compromises – or ‘reconciliation’, to use the legislative parlance. As a result, and in keeping with political tradition, both parties got what neither wanted. The Democrats, however, seem to have walked away with more than their colleagues across the aisle. Republican Senator Richard Shelby, for example, slammed the bill as a ‘legislative monster’, while Senator Dodd offered a more measured response: ‘It is not a perfect bill.’

Indeed, claims that the new measure will kill bank bailouts or prevent a repeat of the 2008 market meltdown are dubious at best. The bill does, in some respects, fall short of expectations, and perhaps too many provisions – or not enough – were negotiated away in the name of bipartisanship. That said, the legislation is not a train wreck either. Given the deluge of provisions issuers must now pore over, legal advice is in demand, and the favorite joke floating around Capitol Hill right now is that Congress has finally managed to pass a jobs bill: full employment for lawyers.

Just the beginning?

The most important point to remember, despite the heated rhetoric, may very well be that this is only the first step. As they say, the devil is in the details, and it is the regulators that the bill quite often saddles with the task of working out those details. In fact, according to Davis Polk & Wardwell’s estimation, the bill promises to keep regulators busy enacting more than 240 rules and producing nearly 90 reports and studies. ‘So this is the big open issue,’ says Steven Shapiro, general counsel and corporate secretary of Cole Taylor Bank. ‘Most of the bill’s bite will come from the regulations and studies, and those haven’t been written yet.’

Two of the more substantive provisions the bill does prescribe involve the creation of two new regulatory bodies: the Financial Oversight Council (FOC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The FOC, a ten-member council chaired by the secretary of the Treasury, is tasked with monitoring the marketplace to identify and deal with emerging systemic risks.

The CFPB – known as the ‘consumer watchdog’, and which ranks among the bill’s most hotly contested provisions – will be led by a presidentially appointed director and granted authority (quite a bit of authority, according to Shapiro) to govern those financial institutions dealing in consumer products and services. For an issuer like Cole Taylor, this means another regulator to contend with. While there is mention that institutions with less than $10 billion in assets will technically fall outside of the CFPB’s remit, remaining instead with their current regulators, Shapiro advises against testing the technicalities. ‘Let’s put it this way: I’m not expecting any free passes,’ he says.

Of the pre-existing regulators, it looks like the SEC, Federal Reserve and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) have come out ahead in terms of expanded jurisdictions and beefed-up authority. A newly bestowed power that has garnered much attention is the Federal Reserve’s ability to regulate interchange fees – something Shapiro says he’s happy about.

Another development that issuers may want to take a closer look at, and one which was brought up during a panel at the Society of Corporate Secretaries and Governance Professionals’ national conference this July, deals with enhanced whistleblower protections. As panel members pointed out, the SEC may have essentially outsourced whistleblower hotlines, as employees can now call the commission directly instead of exploring internal avenues first.

Proxy access

Christmas hath come early, so to speak, for those shareholders on the quest for the alleged ‘holy grail’ of corporate governance: proxy access. Considering the number of proposed shake-ups, it is interesting that proxy access stood out as one of the thorniest subjects throughout much of the debate. An 11th-hour proposal by Senator Dodd to increase the ownership threshold to 5 percent was tossed out, leaving the SEC with the authority to pass proxy access rules in whatever manner it sees fit. Given that the SEC has already indicated its intention to move forward with proxy access, the only substantial change to the status quo this provision seems to make is eliminating the concern about whether the SEC has the authority to sidestep state law and adopt proxy access rules.

Perhaps the biggest surprise to those watching the development of the governance provisions was the elimination of the majority vote provision, which seemed to have garnered little attention throughout the reform process. As David Huntington, a partner in the capital markets and securities group at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, points out, ‘Shareholders care about majority voting. This year it was among the most commonly filed shareholder proposals, so just because it’s not required doesn’t mean issuers can ignore it.’

On the executive compensation front, the majority of the provisions are unlikely to surprise anyone. There is one that seems to have some issuers in a bit of a panic, however: the so-called pay-parity disclosure. According to this provision, companies will now have to provide the ratio of the CEO’s salary to the median salary of all employees, as calculated without the CEO. ‘Personally, I’m unclear what benefit, from a disclosure perspective, can come from this,’ says Elizabeth Powers, a partner and executive committee member at Dewey & LeBoeuf. ‘I think people were a little surprised to see this. They were probably expecting something focused more on comparing the CEO’s pay to that of the other senior officers.’

Michael Melbinger, a partner in the executive compensation practice at Winston & Strawn, echoes Powers’ sentiment, and adds: ‘The pay-parity disclosure will create an incredible new burden. This information does not exist anywhere today.’

Another issue to think about when it comes to the pay-parity disclosure, as Irv Becker, national practice leader of executive compensation at Hay Group, points out, is the potential effect it could have on the now-required say-on-pay votes. ‘It could be that some of the institutional investors will start saying they don’t want to see CEO pay above a certain multiple over median pay, which I think will create some headaches for companies,’ Becker says. ‘Administratively, pay-parity sounds likes it’s going to be a nightmare for companies.

The say-on-pay problem

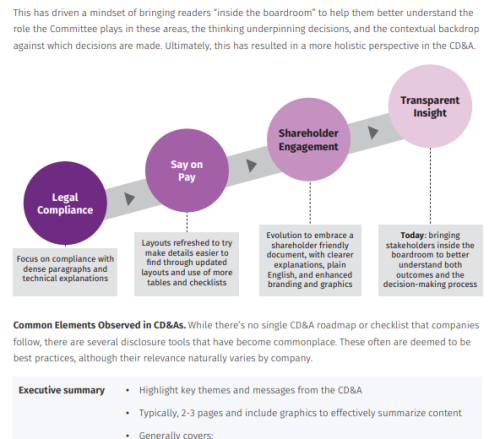

Few will be surprised by the inclusion of say on pay in the final version. Although the advisory vote may seem benign, Becker notes that ‘one of the things that has happened in the UK with say on pay is that, to avoid controversy, many compensation committees have moved to the middle ground on pay design; but if every company’s compensation program looks exactly the same, how do you differentiate your company from your competitors in terms of attracting talent?’ He suggests that this may be a future challenge for issuers in the US as well. ‘How do you maintain the uniqueness of your pay package, and how do you explain and rationalize it in the compensation discussion and analysis [CD&A]?’, he asks.

One pleasant, albeit small, surprise may be the option for companies, subject to shareholder approval, to adopt say-on-pay votes every two or three years, instead of annually. Convincing shareholders – particularly activists who seem to push for a vote every year – to move to a biennial or triennial occurrence may be a bit tricky. On this front, Rhonda Brauer, managing director in the corporate governance division of Georgeson, offered some advice to attendees of the Society of Corporate Secretaries and Governance Professionals’ annual conference in July: raise this question now with institutional investors, and also ask, ‘What would RiskMetrics do?’ Her prediction was that the proxy advisory firm will evaluate these proposals on a case-by-case basis. ‘If a company has good pay practices,’ she said, ‘RiskMetrics may be OK with say-on-pay votes every two or three years.’

At the same conference, Peggy Foran, Prudential Financial’s chief governance officer and corporate secretary, recommended sending letters to the top 50 investors to get their feelings on the issue.

Open questions

One thing Powers suggests for those who are drafting proposals for votes every two or three years is to go back and reread the provisions themselves. She warns that ‘the language is a little unclear and has caused a bit of confusion – not in terms of meaning, but in how the actual mechanics are to operate.’

A minor detail (relatively speaking), but one Powers says her firm is flagging for clients, is the elimination of the broker discretionary vote for executive compensation matters. ‘Broker non-vote matters were, of course, always in the purview of the NYSE, but it looks like a growing pattern here,’ she says. ‘It’s not entirely clear, however, exactly what the scope of the term ‘executive compensation’ is. Does it just encompass the shareholder votes referred to in the bill – say on pay and golden parachutes – or is it broader?’

Although the effect of these provisions may not be felt for a while, when looking at them all together, experts predict they will only increase the importance of regular shareholder communication. ‘It’s the general theme that runs through most of these provisions,’ Huntington says. ‘Companies are going to have to be able to articulate business plans, compensation structures, long-term goals, director nominees and the like to their investors in a clear and comprehensible fashion.’

So what should governance professionals be adding to their summer workload? ‘Start with the easy ones,’ is Powers’ advice. ‘Check out your compensation committee and make sure it meets the existing standards in terms of independence.’ She also suggests putting a hedging policy in place and hammering out the clawback policy sooner rather than later. After that, she says, ‘all you can do is wait to see what the regulators sort out.’

Cheat sheet: most talked-about provisions

Volcker Rule: Prohibits banks from investing more than 3 percent of their capital in hedge funds. The 3 percent allowance was a concession in exchange for Senator Scott Brown’s vote.

Lincoln Amendment: Originally proposed to require banks to spin off their derivatives business. Has since been rendered practically toothless, but in exchange agreement was reached to require banks to move their ‘riskiest’ derivatives into an affiliate.

Derivatives regulation: Many derivatives now have to be traded on an exchange, with heightened reporting requirements and regulation of market participants. Grandfather clause for trades entered before Dodd-Frank enacted.

Winding down TARP: The TARP program is to be immediately shut down, and the remaining funds used in place of an originally proposed (and scratched in 11th-hour negotiations) tax on financial institutions to cover the legislation’s cost.

Notable omission: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac largely ignored – not helpful in bipartisan relations, as Republicans consider the mortgage lenders culprits in the economic meltdown.

Cheat sheet: governance and compensation provisions

Say-on-pay and golden parachute advisory votes: Pending shareholder approval, issuers can choose to hold say-on-pay votes every two or three years. If you choose to do so, experts recommend engaging investors now. Also, remember that the broker discretionary vote has been eliminated. (No further action required by SEC. Effective six months after bill enacted.)

Independence standards for compensation committees and their advisers: Expected to resemble the standards used for the audit committee. Issuers are also required to provide funds for compensation committees to hire outside counsel if they so choose. (SEC to determine definition of independence and then direct stock exchanges to enforce it. Effective one year after bill enacted.)

Changes to executive compensation disclosures: Include charts for pay-versus-performance analysis. Companies will need to spend more time on internal pay equity disclosure, which calls for the ratio of CEO pay to median employee pay.

Clawback policy: Still referred to as ‘recovery of erroneously awarded compensation’ in the bill. The SEC will determine appropriate clawback policies – to include a lookback period of three years for bonus payouts – and the exchanges will enforce them. (No time period for when the SEC must ask exchanges to adopt the rules.)

Disclose employee hedging policy: Decide whether or not those in the company can hedge, and disclose the decision in the proxy statement.

Broker vote eliminated: Applies to executive compensation, but the scope of this is unclear. Allows the SEC to expand this to any other matter it deems appropriate.

Proxy access: SEC allowed to adopt and design rules as it sees fit (no timeframe).

Disclosure of chairman and CEO roles: Largely considered window dressing. Adopt a policy and explain the rationale in the proxy statement.