The hedge fund universe is highly diverse so it can be challenging to make general assessments about it. The variety of hedge funds means IR professionals need to know what they are dealing with.

Equity funds

Equity long-short

The fastest-growing hedge fund strategy and the one most familiar to IROs because, as IR Magazine’s 2017 report The IR view: Hedge funds notes, it is closest to the traditional active management they are used to. This approach essentially takes both long and short positions in securities with the aim of using superior stock-picking strategies to outperform the general market. Long-short funds can be geographical – focused on the US market, Europe or individual countries, for example, or on emerging markets – and also sectoral, focusing on individual industries. Managers can be traditional stock-pickers or use computer models.

Market-neutral

Seen as the most authentic form of hedge fund, these rely on the manager’s skill to equally match long and short positions so that the direction of the market should have no effect on performance, hence the strategy’s name. It’s usually based on pairs trading, with the manager finding similar stocks and buying the one he/she likes and shorting the other. The noted issue with this approach is that there are no perfect pairs.

Short-selling

Probably the most difficult of all hedge fund types for the managers concerned and one IROs need to be aware of. A major problem facing short-sellers is that markets generally go up over the long term. Also, exchanges can impose restrictions on short-sellers and, even when they don’t, it can be difficult to get hold of a stock to sell.

Arbitrage funds

These aim to exploit irregularities in the mispricing of securities. The attraction of arbitrage funds is that they are in theory less correlated with the overall stock market. With many managers analyzing the market, however, arbitrage opportunities are likely to be fleeting. These funds generally perform best after a period of great volatility when there are wider spreads to be arbitraged.

Convertible arbitrage

These funds invest in convertible bonds: fixed-income instruments that give investors the right to switch into shares at a set price. Such bonds go through increases in activity, usually when stock markets are rising. In such conditions, investors like them because they give them a geared play on the stock market – with the bond becoming more valuable when the market price of the shares rises above the price at which the shares can be converted. Companies like them because they carry lower interest rates than conventional bonds.

But hedge fund managers look at these bonds in a more sophisticated way: as a bond with an attached call option (the right to buy an asset at a certain price). Hedge funds believe these call options are often underpriced. As a result, convertible arbitrage managers take advantage by buying the bonds and short-selling the shares. In effect, companies have sold the right to buy shares at too cheap a price. But the space has become somewhat crowded, leading to a withdrawal in capital, resulting in more profitable opportunities.

Statistical arbitrage

The idea behind ‘stat arb’ is that certain securities are linked: for example, with some companies having dual classes of shares, such securities will not always move exactly in line but within a range of each other’s values – say, 90 percent to 100 percent. When the upper or lower bands of that range are reached, a stat arb fund will bet on reversion to the mean. Some of these opportunities may last for only a fraction of a second, so stat arb managers have to be fast. The route to the fastest trades – high-frequency trading – is documented in the Michael Lewis book Flash Boys.

Fixed-income arbitrage

This position is tarnished by the experience of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), the greatly geared hedge fund that controversially collapsed in 1998. LTCM was founded by John Meriwether and a group of fixed-income traders from Salomon Brothers with the idea that some securities in the market are irrationally mispriced. But LTCM’s model did not allow for the kind of market moves that occurred. Nevertheless, there is no reason why fixed-income arbitrage managers should run into the same problems.

There are two main avenues for profit: the yield curve and credit spreads. On the yield curve, as in the LTCM example, fund managers can bet on the ‘shape’. Traditionally, long-term bonds have yielded more than short-term bonds – if the shape does not conform to this pattern, the fund managers can bet that wide spreads will narrow or that narrow spreads will widen. It is, however, easier to bet on narrowing than on widening because of the way the trade works: narrowing involves buying a higher-yielding bond and shorting a lower-yielding one.

This approach was given a lot more flexibility by the development of credit derivatives, particularly credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations. The former allow investors to insure their bonds against default, or bet that default will occur; the latter slice portfolios of bonds into different tranches, based on risk. The additional risk within these approaches contributed to the 2008 financial crisis.

Directional funds

Global macro managers

Global macro managers dominated the hedge fund industry in the early 1990s, with big names George Soros, Julian Robertson and Michael Steinhardt ruling the space, but have since become less significant. Global macro can be hard to define. In his book, Inside the House of Money, Steven Drobny writes: ‘Global macro has no mandate, is not easily broken down into numbers of formulas, and style drift is built into the strategy as managers move in and out of various investing disciplines depending on market conditions.’

Nevertheless, there is today a great deal of cynicism among investors about the ability of hedge fund managers to make big successful bets on macro events such as devaluations, on which Soros made his name. Moreover, with the euro, there are fewer fixed exchange rates to aim at.

Event-driven

Distressed debt

Managers in this area invest in bonds or loans issued by companies that are in trouble, hoping to exploit the fact that investors generally panic when companies look in danger of default, which drives the bond price down to depressed levels. Managers here want to own debt that earns more than the cost of leverage and hope that the possibility of default is less than the market thinks.

Merger arbitrage

Although this has an arbitrage label, it is really an event-driven approach. As IR professionals know, nothing gets the stock market more excited than a big takeover. Not only does the share price of the target price rise, but the shares of other comparable companies or potential targets tend to rise as well. Merger arbitrage

funds are often betting on bids to go through so they have an interest in pushing the target company to accept the offer. This in turn may well lead to more takeovers occurring than happened in the past – a point hedge fund critics are regularly taking up.

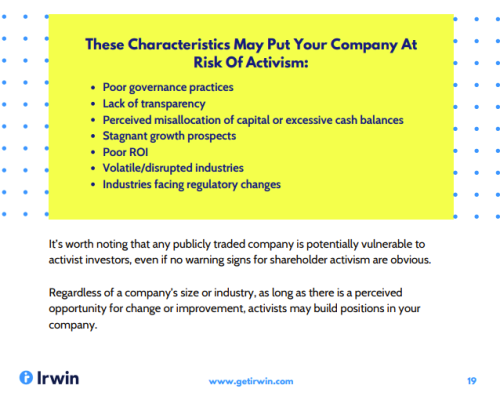

Activist funds

For IR professionals, and the wider investor world, this is the most controversial type of hedge fund, as its philosophy is that company boards need to be pushed into action. With a small stake, activists can get a lot of leverage over executives, who may fear a shareholder revolt if they do not act. Activists have traditionally been a force in the US and this has moved to Europe, where shareholders were traditionally seen but not heard.

Multi-strategy funds

Multi-strategy covers two distinct trends: the first relates to mangers who diversify their businesses to move from one strategy into another. The second covers individual multi-strategy funds that switch money on their clients’ behalf: an asset allocator sits at the center of the structure, deciding which strategies and which managers are likely to produce the best future returns. This is all good in theory though its success depends on two factors: the allocator giving money to the right people and the underlying managers being worth giving money to.

Summing up a measured IR approach to hedge funds, Victoria Hyde-Dunn, director of investor relations at 8x8, says: ‘You shouldn’t judge a book by its cover – so apply the same objective logic when engaging with hedge funds as you would with other investors.’