The impact of raising Brazil's sovereign debt to investment grade was stifled by recession. A year on there are signs of recovery.

In a region renowned for its defaulters, Brazil has done rather well of late. The country hasn’t formally run out of cash since the 1980s, while others in South America, like Ecuador, are still playing cat and mouse with international investors. This led to Standard & Poor’s, the credit ratings agency, upgrading Brazil’s foreign debt to investment grade status in April 2008, which commentators predicted would boost interest in the country’s issuers. Fitch, another ratings agency, followed with its own investment grade rating a month later.

Two investment ratings meant a wider range of international investors, including some big US pension funds, would be able to pour money into the country’s stock market. The ratings also gave the country an overall credibility boost on the international stage, prompting Bovespa, Brazil’s benchmark index, to hit record highs.

Everyone knows what actually happened next, however: the financial crisis entered its second and decisive phase. Brazil, like every other country in the world, saw its stock market collapse. It ended 2008 down 41 percent.

All this means it is pretty tough to gauge the impact of the investment grade ratings, which – at time of writing – Brazil maintains. Risk premiums on government and corporate debt should have fallen after the upgrades; instead they soared. The credit crunch has  distorted a lot of the data, according to Ricardo Leoni, capital markets superintendent at the Brazilian unit of Santander, the Spanish bank.

distorted a lot of the data, according to Ricardo Leoni, capital markets superintendent at the Brazilian unit of Santander, the Spanish bank.

Comparable strength

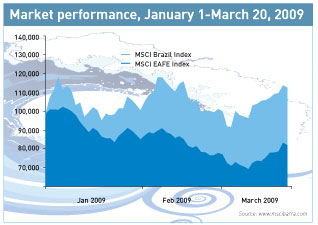

But when you compare Brazil’s performance to those of its peers, in both developed and emerging markets, it doesn’t look too bad. During the first months of 2009, the MSCI Brazil Index easily outperformed the MSCI EAFE Index, a benchmark for non-US stocks (see Market performance, right).

Bigger firms have also enjoyed the ongoing corporate bond bonanza: Petrobras, the state-owned oil giant, issued 10-year bonds worth $1.5 bn in February 2009 in a sale that Reuters says was three times oversubscribed.

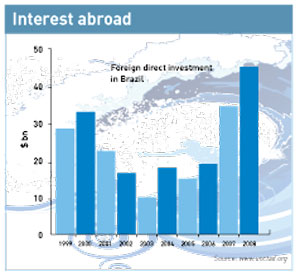

And Brazil’s banks have managed to keep their heads above water, while many in other countries have sunk without trace or needed emergency resuscitation. Earlier this year Banco Itaú and Unibanco, which are merging to create Brazil’s largest private sector bank, together surpassed the market capitalization of Bank of America and Citi combined. Furthermore, 2008 set a new record for foreign direct investment (see Interest abroad, below).

Going strong

From this evidence it is clear Brazil is coming through the crisis well and remains attractive to foreign investors.

‘When you look at day-to-day research from the investor side and the equity side, it’s clear the perception of Brazil has changed dramatically,’ comments Evandro Pereira, head of Latin American capital markets for UBS Pactual. ‘But this is not necessarily a consequence of the investment grade status. On the contrary, I think the investment grade status just confirmed something the market was already pricing in.

‘You can see that in the performance of the Brazilian currency since the start of 2009. It’s relatively stable compared with what has happened to other currencies around the world, like the British pound or even the euro. Also, from an investor perception point of view, I think everyone gives credit to Brazil for what it has done in the last 10 years in terms of solving its most important problems related to its balance of payments.’

Of course, nowhere is out of the woods yet. Global markets have mostly stalled or fallen back since the start of the year; so far, Brazil is one of the exceptions. By March, S&P had placed around a quarter of sovereign-rated countries on negative outlook.

But the country is relatively well placed to ride out the economic downturn, a fact reflected by its ratings upgrades last year. After all, upgrades are a consequence of investment that has already occurred, not a cause of it, notes Paulo Vieira da Cunha, a former director at Brazil’s central bank who is now head of emerging markets research at Tandem Global Partners in New York.