Earnings guidance remains popular despite tough economic conditions

When the likes of Unilever, Coca-Cola or Google stop furnishing earnings guidance, the strategic about-face makes headlines. Some applaud management as courageous; others (such as analysts and investors) may wring their hands, realizing that an important source of information has disappeared.

In spite of the ink devoted to companies that opt for a news blackout on earnings forecasts, recent research shows the majority of companies continue to convey some viewpoint on future financial performance to their investors.

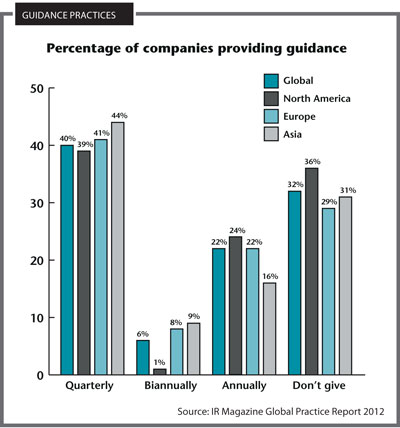

Globally, just over two thirds – or 68 percent – of companies provide earnings guidance to investors at some point during the year, according to the IR Magazine Global Practice Report 2012. This represents a 3 percent increase over the number of companies providing earnings guidance in 2011.

The research also finds that the most popular interval for giving guidance is quarterly, with 40 percent of firms communicating about their performance every three months.

One reason for a massive re-evaluation of earnings guidance practices is the global financial crisis and subsequent economic recession, says Baruch Lev, professor of finance and accounting at NYU’s Stern School of Business.

To illustrate, he notes that between 2007 and 2008 there was a 30 percent drop in earnings guidance furnished by US companies. More recently, he says, a handful of companies have begun giving earnings guidance again, but those that opted out haven’t returned in dramatic numbers.

Although everyone notices when a major company jumps off the guidance bandwagon, most remain stalwart fans of the practice. Chris Welton, senior vice president of investor relations at VINCI, a Paris-based construction concession company, points out that he gives both annual top-line and bottom-line guidance in early February, narrowing down the ranges six months later.

‘Our shareholders are like airplane passengers,’ says Welton. ‘They ask, How good is your airplane? and we tell them it has a solid engine, terrific maintenance, great pilots and comfortable interiors. If they buy a ticket and ask where we’re going, and we say, We’re not going to tell you, that’s the equivalent of not giving guidance. You’ve got to give guidance.’

Even though Welton acknowledges that US investors prefer quarterly EPS guidance, however, his company provides net income guidance with some discussion of other factors that could influence results. ‘We prefer to give net income guidance because the share counts can change,’ he explains.

Qualitative data gains favor

The debate over quantitative versus qualitative guidance varies by location. In February 2013 the IR Society in the UK found that fewer than 10 percent of FTSE 100 companies provide quantitative earnings guidance, while 65 percent give qualitative guidance – typically, narrative directional guidance on EPS, revenue, profit or other operational metrics.

Anju Marempudi, founder and CEO of eventVestor, which conducted the research for the IR Society, points out that most of that 10 percent of FTSE 100 companies providing quantitative earnings guidance are either listed in the US as ADRs or have sizable American holdings.

The IR Society strongly endorses the practice of providing qualitative guidance over EPS numbers, and the head of the society practices what his organization preaches. John Dawson, the society’s chairman and head of IR for London-based National Grid, has furnished guidance on metrics that contribute to earnings during his past two years at the company.

He acknowledges that the line between qualitative and quantitative guidance sometimes blurs. A company might, for instance, give numerical ranges for factors that influence earnings without actually predicting an EPS number.

The IR Society also contrasts the practices of UK and US companies, although there’s at least some evidence US companies are gravitating toward providing more qualitative guidance.

‘Most companies don’t like to provide specific EPS targets and are looking for ways to move away from that practice,’ explains Tim Koller, expert principal of the corporate finance practice at McKinsey & Company. ‘We’re seeing more focus on the operational side than on all the nitty-gritty things that may affect an accounting EPS number.’

As an example, Koller points out that some oil firms are offering a production range and concrete numbers for oil exploration expenditures. ‘Investors realize companies don’t control oil prices,’ he says. ‘What they can control is how much oil they’re bringing out of the ground and how much they’re spending to find new oil.’

A company’s willingness to forecast earnings numbers also varies by industry. Enbridge, a Canadian energy distribution and transportation company, gives annual earnings guidance and places a very specific range on EPS predictions, according to Jonathan Gould, director of investor relations. He believes guidance is a way for Enbridge to demonstrate its overall investment proposition.

‘It’s a comfort for investors and the analyst community to see that yet again and for another year, Enbridge is providing the same stable earnings guidance – and yet again, every year, Enbridge has met that guidance,’ he says. ‘It reinforces our message.’

A path to poor decisions?

One argument for abandoning strict EPS guidance is that companies locked into a number might make unwise decisions in order to ensure the guidance pans out. As Dawson puts it: ‘The IR Society believes detailed quantitative guidance can encourage short-termism and act as a hostage to fortune.’

Koller agrees. ‘We’ve seen a number of companies that feel like they have to meet the number they put out there,’ he says. ‘They’ll cut expenditures on marketing or product development to meet that number. They’re unhappy about it, but they feel they have to do it. They feel if they miss a quarter, disaster will strike. I’ve heard horror stories about the kinds of things companies cut to meet the numbers and it can play out over four, five or even six years.’

Some companies, such as Unilever, have famously discontinued earnings guidance altogether. In February 2009, a few months after Paul Polman became CEO, he announced the change.

One of the company’s reasons for doing this, explains Roger Seabrook, vice president of investor relations, was the difficulty of providing robust guidance during the financial crisis.

More important, adds Seabrook, was the sense ‘that chasing quarterly targets is simply a bad thing to do.’ By refusing to issue guidance, Unilever hoped ‘to break the cycle’ of focusing too intensely on short-term results.

On the day Unilever announced it was discontinuing earnings guidance, its stock price dropped 6 percent. But Seabrook says the company attributed the drop to the pressing economic concerns Polman aired during his announcement rather than to the guidance decision itself.

Seabrook also notes that the analyst community’s reaction to the news was mixed, ‘but the majority of analysts seemed to understand what we were trying to achieve.’

The decision certainly hasn’t hampered the stock: Unilever’s share price is up by more than 50 percent since Polman took over on the back of strong business performance.

Although many believe earnings guidance can easily lead to bad corporate behavior, the evidence is still far from conclusive. Andrew Call, assistant professor of accounting at the University of Georgia, is testing this proposition by examining 33,000 sets of financial results between 2001 and 2010.

Call and his colleagues paired US companies that gave quarterly guidance with firms that didn’t and looked for any signs that they were managing earnings, such as abnormal accruals and discretionary revenues.

‘We found that firms issuing short-term earnings guidance are less likely to manage their earnings than firms that don’t provide guidance,’ says Call. He suggests companies concerned about missing earnings benchmarks might be giving earnings guidance ‘as a way of walking analysts down’ from predictions that are unlikely to prove correct.

The upside

What’s more, some argue that earnings guidance brings distinct benefits. Jason Golz, director at the Brunswick Group, points out that providing earnings guidance can serve as an important factor in instances of shareholder litigation.

He says companies that can prove they’ve communicated transparently with investors find themselves in a far stronger position should they ever face litigation.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth Sun, director of corporate communications and head of IR at TSMC in Taiwan, believes earnings guidance is one ingredient in a robust relationship between a company and its investors. ‘Companies can build a loyal, long-term shareholder base by being transparent, honest and showing the quality of the management,’ she says.

Sun places enormous stock in the reliability of the guidance she gives. TSMC, she notes, makes detailed financial forecasts on a weekly basis.

‘By the time we’re about to give quarterly guidance, we can look at the weekly and monthly internal forecasts and see whether those numbers have been stable or erratic,’ she says. ‘If there have been many changes lately, then when we give our guidance, we’ll be a little more conservative.’

Simply giving guidance numbers and not providing context might foster an emphasis on the short term, which Sun acknowledges. But she sees earnings guidance as an important part of a much fuller conversation.

‘If you explain the factors that go into the numbers, gradually, over time, your investors understand you better,’ she says. ‘And they will stay with you longer.’

Regional differences

According to the IR Magazine Global Practice Report 2012, North American companies are the least likely to provide earnings guidance – although not by an especially large margin. The report finds that 36 percent of North American companies never provide earnings guidance, slightly higher than the 31 percent in Asia or 29 percent in Europe that don’t do it.

Of the three regions, companies in Asia have been the most likely to take up earnings guidance in the recent past: the number of holdouts declined by 10 percentage points between 2011 and 2012.

One reason for the regional discrepancies is different regulations. Dawson points out that the UK’s Takeover Code might dissuade companies from giving earnings guidance because it could come back to haunt them in an M&A situation. Similarly, Maureen Wolff, president and partner at Sharon Merrill Associates, points out that the SEC has recently begun ‘cracking down on Regulation G for forward-looking guidance.’ For this reason, she suggests, some US companies might shy away from providing EBITDA guidance and instead give forecasts about business drivers, such as gross margins or depreciation.

Similarly, Maureen Wolff, president and partner at Sharon Merrill Associates, points out that the SEC has recently begun ‘cracking down on Regulation G for forward-looking guidance.’ For this reason, she suggests, some US companies might shy away from providing EBITDA guidance and instead give forecasts about business drivers, such as gross margins or depreciation.

TSMC prides itself on its financial guidance but does not give EPS numbers for regulatory reasons. ‘Taiwan’s regulators say that if a company guides the top line and bottom line together, it has to announce at least a full-year audited financial forecast within three days – and nobody wants to do that,’ says Sun, laughing.

On the other hand, TSMC does provide quantitative guidance. ‘Six or seven years ago, we requested that the regulators allow us to guide revenue all the way to operating profit margins, and we’d stop there without guiding the EPS,’ says Sun. ‘The regulators agreed, and ever since we have guided revenue, gross margins and operating profit margin rate.’

Tough decisions

Companies toying with the idea of discontinuing guidance often fret about the hit their stock prices might take – and Lev believes these fears are well founded.

‘Several studies show that when companies announce they’re stopping guidance, the stock price on average goes down by more than 5 percent,’ he points out. Nor does the pain necessarily end there: Lev notes that financial analysts sometimes desert firms that discontinue guidance.

Given the potential downside of changing course on earnings guidance, it’s perhaps no coincidence that NIRI’s 2012 guidance survey finds 60 percent of US companies that don’t give guidance have never done so. Although some managers might focus on the drawbacks of giving guidance, most of them feel there are worthwhile benefits.

And in the end, avoiding guidance doesn’t eliminate the pressure to make numbers. Even if a company opts out of issuing guidance, says Golz, the expectations around quarterly results will still exist because analysts and even retail investors will create consensus estimates.

In other words, companies can withdraw from the earnings guidance game, but it won’t withdraw from them.

Different strokesPractically nothing within the earnings guidance debate is clear-cut. Even those public companies that provide guidance do so in vastly different ways. Take, for instance, how often guidance is issued. In its research, IR Magazine found quarterly guidance to be the most popular, with 40 percent of companies choosing this option. Second most popular is annual guidance at 22 percent, followed by biannual guidance at 6 percent.Here, too, guidance practices assume a regional flavor. In Europe and Asia, biannual guidance is given 8 percent and 9 percent of the time, respectively. In North America, on the other hand, half-yearly guidance is practically unheard of, with just 1 percent of companies providing it. Lisa Rose, senior managing director at Dix & Eaton in Cleveland, Ohio, has seen a trend among smaller and mid-cap firms in the US to give greater consideration to annual guidance. ‘Companies want to keep investors focused on the long term rather than on short-term results,’ she says. And for IROs and CFOs who are skittish about annual guidance, Rose recommends exploring an even more expansive time horizon. ‘When companies don’t feel comfortable with guidance, we’ll talk to them about putting out three-year targets,’ she says. ‘We’ll ask them, How big are you aspiring to be? Talking three years into the future gives them a little more comfort and ease.’ Another key consideration is how specific companies are willing to be with the quantitative guidance issued. Most companies eschew specifying an actual target and instead provide a range, but there’s an art to this, too, says Rose. ‘You don’t want a range so big you can drive a truck through it,’ she points out. ‘It doesn’t have to be a super-tight range, but it can’t be huge.’ Finally, even the amount and specificity of quantitative guidance may be changing – although changes like this don’t necessarily show up in research reports. ‘Companies that give guidance are providing more context for what their assumptions are,’ observes Maureen Wolff, president and partner at Sharon Merrill Associates. ‘When they provide guidance, they’re also helping educate investors on the drivers of the business.’ |