EC Green Paper outlines the future of corporate governance for European financial institutions

A new European Commission (EC) Green Paper has launched a summer of debate on corporate governance at financial institutions, and IROs may soon be facing a whole new breed of involved and ‘empowered’ shareholder. Calling for ‘significantly strengthened’ corporate governance checks and balances in response to the financial crisis, the executive arm of the European Union has put forward myriad options for reform. But its take on the role of shareholder involvement in risk management is of most interest to IROs.

‘The financial crisis has shown that shareholders have not been vocal on a number of key issues, such as remuneration policy, strategy and risk appetite,’ note EC documents accompanying the Green Paper. ‘In many cases, [shareholders] failed to identify weaknesses in boards and management and curb very aggressive growth strategies, and did not prevent remuneration policies that included incentives for excessive risk taking and short-term profitability’.

The 19-page Green Paper says shareholders’ lack of interest in corporate governance raises serious questions about ‘the effectiveness of corporate governance rules based on the presumption of effective control by shareholders for all listed companies.’ Indeed, the commission plans a broader review in the autumn covering listed companies in general. That report will highlight the distribution of duties between shareholders and boards with regard to supervising senior management, board composition and social responsibility.

The EC is considering several tools to prod institutional investors into a more prominent risk management role, including voting disclosure, adherence to best practice stewardship codes, regular ‘discussion platforms’ between shareholders and companies in which problems can be ‘discussed and diffused’, and shareholder identification to encourage shareholder engagement while reducing ‘abuse’ connected to empty voting.

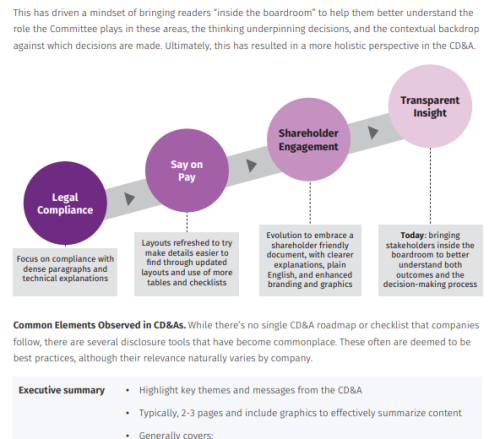

The EC also wants shareholders to be provided with better information on risk. According to an EC Working Paper, ‘information made available to shareholders by financial institutions, particularly on risk, is considered to be too lengthy and complicated for shareholders to assess and understand. There is a need to make company information more shareholder-friendly.’ The report also notes that shareholders have indicated that more comprehensive information is needed on risk appetite, key risk exposures and the risk management system.

Evolving external governance

Peter de Proft, director general of the European Fund and Asset Management Association, says that although it is too early to provide detailed comments, his group gives the highest priority to the EC Green Paper. ‘The idea of external governance is an interesting evolution,’ he says. ‘Asset managers didn’t cause this crisis. Just look at the financial reporting of financial institutions: did they give the real risks? The only thing we could do before the crisis was vote with our feet. It is questionable whether such things as reporting on voting policies would have prevented the crisis.’

In a speech given in March, Liz Murrall, director of corporate governance and reporting at the UK’s Investment Management Association, noted the limitations of what shareholder oversight can realistically achieve. ‘[Fund managers] do not have insider status and are not privy to the same information as the executive or the non-executive directors,’ she said. ‘It’s now apparent that boards and management of financial institutions [often] failed to appreciate fully the risks on their balance sheets, thus fund managers could not have been expected to, either; this was not a problem that could have been avoided by better engagement.’

Even if more engagement by fund managers was desirable, Sarah Wilson, managing director of UK-based governance research and proxy voting provider Manifest, believes the Green Paper’s proposals, while a step in the right direction, are unlikely to dramatically stimulate such engagement.

‘There are lots of players on this stage and the EC just wagging its finger at shareholders is simplistic and misses the point,’ she says. ‘For example, many shareholders and fund managers want to do more but are hindered by proxy voting infrastructure issues that are the fault of banks [and their custodial units] themselves. Ownership is not transparent and the operational barriers to cross-border voting are ridiculously Byzantine. It’s alright to get G20 brownie points for beating up on stakeholder groups but that doesn’t actually give those groups the tools to do the job.’

Along with fixing the proxy plumbing, Wilson says a pan-European stewardship code could go a long way to solving the ‘engagement’ problem. ‘There is no shortage of disclosure,’ she adds. ‘What we need is the joining up of the disclosure and the action.’

Is there a Plan B?

And if banks and other vendors of financial services don’t get their act together? Speaking to market participants this spring, Michel Barnier, the EC’s Internal Market and Services commissioner, commented: ‘It is our common responsibility to... defend our internal market from the populist and protectionist tendencies that could emerge if we fail.’ His pejorative use of the term ‘populist’ presumably referred to nationalistic demagoguery rather than political ideas that furthered ordinary people’s interests.

The Green Paper’s draft proposals, open for comment until September 1, also include suggestions aimed at improving corporate boards, regulating management and director pay, expanding the role of supervisory authorities and external auditors, and the establishment of a ‘risk culture’ at all levels of a financial institution. The governance reform plan ties into a raft of initiatives aimed at meeting G20 commitments to strengthen transparency, responsibility and capital requirements.