Companies are increasingly being pressured to prioritize short-term goals, but a campaign to persuade them otherwise is gaining momentum

In April, 500 letters left BlackRock’s New York headquarters and were scattered across the US. Destined for the CEO’s office at every S&P 500 firm, they called for listed companies to resist the pressure to meet short-term financial goals and to put long-term value creation first instead.

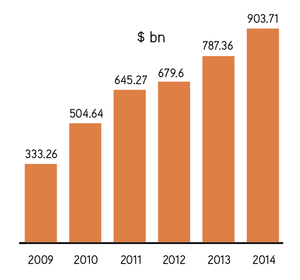

The letter – authored by BlackRock’s own chief executive Larry Fink – helped rekindle debate over areas like activism and capital allocation. Companies spent $900 bn on dividends and buybacks last year, while underinvesting in innovation, staff and essential capital expenditure, he fretted. Fink’s intervention is part of a wider movement that wants to push back against short-termism in its various forms. Central to that mission is the Focusing Capital on the Long Term (FCLT) project. Founded two years ago by McKinsey & Company and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), it seeks to help investors and companies with advice and practical tools.

| At a glance The problem A range of factors – from quarterly financial goals to activism, the media and government policy – are increasing the pressure on companies and investors to prioritize short-term over long-term objectives, according to Larry Fink of BlackRock and the Focusing Capital on the Long Term (FCLT) project. A growing campaign Fink’s letter to CEOs in April this year highlighted the spread of short-term thinking and helped put debates over buybacks, shareholder activists and other areas back on the agenda. Meanwhile, FCLT’s co-leader Dominic Barton raised the issue with IROs at NIRI’s annual conference. The advice Fink advises companies to remember that they should put the interests of long-term owners first. FCLT has specific advice for investor communications: spend more time talking about the long term and produce new ‘health metrics’ tracking sustainable value creation. |

FCLT has gathered pace this year, holding a conference with 120 attendees in March. In addition, Dominic Barton, McKinsey’s global managing director and leading voice on short-termism, helped raise its profile among IR professionals when he spoke at NIRI’s annual conference in June. The scope of the project’s aims is daunting, however. In its sights are, to name but a few targets, excessive buybacks, shareholder activists, quarterly reporting, impatient boards, the 24-hour media and unhelpful government policy. It’s just as well FCLT is not focused on results in the short term.

Fink’s letter should not have come as a surprise to companies. He wrote to all CEOs and chairmen last year on a similar theme, asking for better engagement between companies and investors to drive long-term performance. The most recent missive, however, has a more campaigning tone. In it he lists the various factors he views as contributing to an ‘acute pressure, growing with every quarter, for companies to meet short-term financial goals at the expense of building long-term value.’

S&P 500 buybacks and dividends Source: S&P Capital IQ |

The letter draws particular attention to the high level of buybacks and dividends pouring forth from S&P 500 coffers. That figure of $900 bn has nearly tripled in five years, driven by huge programs from the likes of Apple ($140 bn) and GE ($50 bn). Fink is worried not so much that the figure is high, but rather that the money could be better used elsewhere.

The latest letter also mentions the proliferation of shareholder activists. Activism is noted as just one among a number of factors but – unsurprisingly – it became one of the main talking points following publication of the letter. Fink does not tar all activists with the same brush – he says some are aligned with companies’ long-term interests and have pushed for productive changes – but he does urge corporate executives to remember that long-term owners should be put first.

Refreshing, not revolutionary

These issues are already well-worn topics of debate among companies in the North American market and beyond. Fink’s intervention, however, should help to remind corporate leaders about their long-term obligations, says Robert Berick, managing director and head of the IR practice at Ohio-based Falls Communications. ‘My sense is that having a prominent investor like Fink encourage companies to invest in the future in his open letter was seen as refreshing rather than revolutionary,’ he says. ‘By that I mean it was a long-awaited affirmation that management does have an obligation to build and maintain a business that can successfully compete over the long term.’

| Long-term value summit: quick takeaways The Focusing Capital on the Long Term project recently released the preliminary highlights from its Long-Term Value Summit in March. Below we’ve pulled out a few talking points:

|

Andrew Simanek, director of IR at HP, well understands the difficulties of balancing the short term with the long. Five years ago HP had a bad reputation for capital management following a series of questionable decisions around M&A, buybacks and R&D. But the tech firm has worked hard to re-establish trust with investors through a new returns-based framework for capital allocation (see HP Q&A: A new framework for capital allocation, below).

Like Berick, Simanek views Fink’s letter as a timely reminder for companies. ‘His point was that sometimes investors come in and may just push for some type of short-term financial engineering that may briefly help the stock price,’ he comments. ‘But that may not ultimately be the best for the long-term health of the company because, especially in the tech industry, if you don’t invest in R&D and remain a leader from an innovation standpoint, you run the risk of becoming a dinosaur in five years.’

Capital project

While not a founder, Fink is now part of FCLT and sits on its advisory board. Launched in 2013, the project started by bringing together 20 senior figures from the corporate and investment worlds to develop strategies and tools that would help refocus markets on long-term aims.

The organizers point to various pieces of research to highlight what they view as the negative way in which short-term pressures are affecting companies. On the investment side, they note that average holding periods on the NYSE have fallen from several years to under a year over the last three decades. And on the corporate side, McKinsey surveys have found that 84 percent of senior executives feel more pressure to show financial results within two years, while 78 percent of CFOs admit they would sacrifice long-term investment opportunities in order to smooth earnings.

The findings chime with Berick’s take on today’s market conditions. ‘I think short-termism is a real problem in that it has made management teams and their boards of directors increasingly risk-averse – particularly when it involves a significant capital investment,’ he says.

FCLT kicked off this year with its Long-Term Value Summit in New York, where it presented four areas for action: portfolio strategies, active ownership, shifting the focus of boards and – of most interest to IROs – improving the dialogue between investors and corporations. So how could the dialogue improve?

First of all, companies need to make sure they actually have a long-term strategy, which FCLT defines as one lasting at least five years. Executive teams should then make sure they are talking about their long-term plans and using the right kind of metrics to track progress.

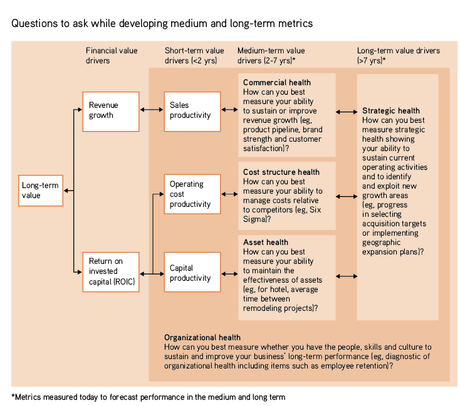

Unfortunately, the right metrics may not exist, however. Indeed, FCLT encourages companies to come up with new ones that can measure sustainable performance over long periods, which it dubs ‘health metrics’. These could focus on areas such as innovation, staff turnover, product pipeline and community trust. The initiative has created a flow chart to help develop new yardsticks for performance (see Health metrics, below).

| Health metrics Taken from 'Straight talk for the long term', March 2015  Source: Focusing Capital on the Long Term. Click for larger version. |

Perception problems

Few would argue that taking a five-year-plus view is a bad thing, of course. But some of those blamed for today’s corporate myopia – shareholder activists, for example – maintain their actions lead to stronger companies in the long run, and recent research from The Economist backs up this stance.

In February, the publication revealed the results of a study into the 50 largest activist positions since 2009. In the majority of cases, ‘profits, capital investment and R&D have risen’, and there is little evidence of the common charge of asset stripping, The Economist says.

Another challenge facing Fink and the FCLT project is that some executives don’t accept there is a major problem. One insight into the C-suite mind-set came at this year’s NIRI conference during the CEO panel session, which was held directly after Barton’s talk on short-termism. The three corporate bosses – Bob Eck of Anixter, Greg Brown of Motorola and Michael Ball of Hospira – all said that short-term pressures hadn’t had a significant impact on the way they run their businesses. ‘I don’t really think things have changed that much,’ said Ball during the session. ‘The role of the CEO is the same now as it was 10 years ago, maybe 15 years ago. From a communications standpoint, maybe with investors it’s changed a little bit, but certainly with the customers it remains the same; with employees it remains the same.’

Brown noted, though, that the growth of activism is having a significant impact on how companies operate. ‘That brings a dynamic that’s different in its frequency and prevalence today,’ he commented, referring to the major campaigns at Motorola by ValueAct Partners and Carl Icahn.

Simanek agrees that, aside from activism, the onset of short-term pressures hasn’t fundamentally changed the way in which companies conduct themselves. ‘I think it’s always a challenge,’ he says of the battle between short-term and long-term interests. ‘Is it worse today than it was a couple of years ago? Maybe at the margins.’

He adds that you must consider the short as well as the long-term perspective to be successful. ‘It’s a balance,’ he explains. ‘For more mature companies, investors will often bail if you focus solely on long-term investments at the expense of short-term results or capital return to shareholders. They simply won’t have the patience to see whether your R&D investments paid off – even if they ultimately do and prove to be the best use of capital. It’s about finding that happy medium.’

|

HP Q&A: A new framework for capital allocation |

This article appeared in the Fall edition of IR Magazine