Companies are facing a record number of climate-related resolutions, growing divestment campaigns and questions over carbon risk that go to the heart of their strategies

We must take stronger action, more urgently. That is the message from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which released the second part of its fifth report into global warming in March.

While the findings of the fifth report provide fuel to advocates and skeptics alike in the climate debate – for skeptics, they note that temperature rises have slowed over the last 15 years – the authors conclude that dangerous levels of global warming are on the horizon if we don’t change our ways soon.

'Hardly any of the investors that have divested have done so on ethical grounds’ – Craig Mackenzie, head of sustainability at Scottish Widows Investment Partners |

For investors, the impacts of global warming, along with the threat of government action to curb it, have been real enough for them to view climate change as a key risk to their portfolios for many years. Today, however, they are putting more pressure on companies than ever before – pressure to talk about emissions, curb damage to the environment and explain how they will adapt their strategies as curbs on carbon production start to bite.

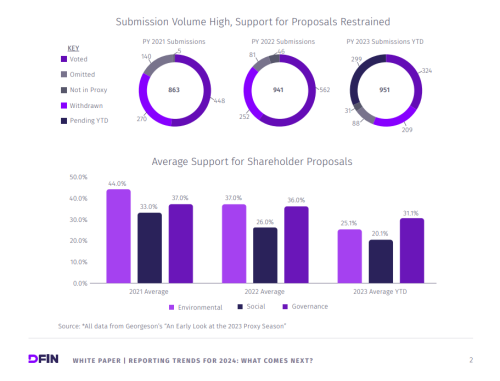

The uptick in investor pressure is underlined by the record number of resolutions filed in the US this year over climate change-related issues. As IR Magazine went to press, institutions had filed 142 resolutions calling for action at 118 companies, according to sustainability lobby group Ceres.

Firm resolutions

Tim Smith, who heads up ESG engagement at Boston-based Walden Asset Management and acted as one of the lead filers for those resolutions, says investors are expanding the range of topics they want to engage over, citing resolutions on carbon asset risk and political lobbying. ‘There is this irony of companies saying, We’re very concerned about climate change, and yet they support a group that is trying to stop very important climate initiatives at the state level,’ he observes.

Smith also points out that resolutions are just one sign of investor engagement. ‘There are scores of examples of investors reaching out to companies for dialogues or meetings or sending them letters,’ he expands. ‘I’ll just give you an example: we led an initiative with companies this year, asking them to set greenhouse gas goals and [devise] plans for reducing greenhouse gas. We sent letters to 30 companies in our portfolio, and followed up with about 10 that got resolutions.’

A handful of companies have lost resolutions over ESG issues but hardly any come close to receiving majority support. For Mindy Lubber, president and CEO of Ceres, that is beside the point. She says the aim is not to win votes, which in any case are advisory in nature, but rather to send a signal to the company’s management.

‘Votes above around 25 percent send a very strong signal to company management that it needs to take action,’ she states. ‘Many individual investors simply vote with management because they don’t pay attention to proxy voting or they are invested through mutual funds that tend to vote with management.’

If resolutions are one way to put pressure on companies, another is the threat of divestment. Those calling for divestment from fossil fuel companies received a boost in March this year when Norway’s two governing political parties set up an expert committee to examine investments in oil, gas and coal by the country’s $850 bn sovereign wealth fund (SWF).

The committee will decide whether to address climate change through engagement or by finding ‘responsible criteria for exclusions,’ says Svein Flåtten, Conservative MP and spokesperson for financial affairs. ‘The fund already abides by a list of ethical guidelines, mostly centered on excluding companies that violate human rights, manufacture weapons or produce tobacco, but with provision for those that contribute to severe environmental damage.’

Going green

Later in March, Norway’s Prime Minister Erna Solberg revealed plans to invest more of the fund into renewable energy companies in order to meet 2020 climate change targets. Fossil fuel holdings currently represent 8.4 percent of the SWF’s equity investments, worth around $44 bn. Such is the fund’s size that if it were to divert just 5 percent of its total holdings into environmentally friendly companies, it would easily become the world’s largest green investor.

Ben Caldecott, program director and research fellow at Oxford University’s Smith School of Enterprise and Environment, points out that the Norwegian SWF’s announcement has at the very least ‘raised the profile of divestment as a real possibility. If it decides to do so, and the basis of its decision is material risks or that as a nation it wants to hedge its current oil and gas exposure, that could have a significant impact.’

As part of the Smith School’s extended study of stranded assets (see Climate chat, below, for definitions), Caldecott and his colleagues have written a paper that examines the impact of divestment campaigns on the valuation of fossil fuel assets. It finds there are three main aims of divestment: to make sure natural resources are left in the ground, to pressure companies into ‘transformative changes’ in order to reduce CO2 emissions and similar, and to pressure the government into introducing new legislation.

Drawing on statistics from campaigns throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the report finds that all divestment campaigns studied were successful in ‘securing changes to regulation’ in one way or another.

‘In the end, these are perhaps the changes that matter most,’ Caldecott notes. Even if engaged investors divest all their holdings, he explains, the impact on stock price is limited, and any stock given up is likely to find its way into the hands of neutral investors.

The most important effect to consider is that of stigmatization, both for individual companies and industries at large. Through new legislation, campaigns can have a profound effect on capital flow and investor sentiment, which can in a number of situations lead to institutions going significantly underweight on targeted sectors.

‘Stigmatization poses a far-reaching threat to fossil fuel companies – any direct impacts of divestment simply pale in comparison,’ notes Caldecott’s report.

Making connections

In Caldecott’s experience, connecting with investors over climate change comes down to convincing them you want to take action over their concerns. ‘Take immediate action to get into the top quartile for your sector, engage with your owners and engage with external stakeholders – including campaign groups and non-governmental organizations,’ he advises.

One of the best-known divestment campaigns is the Fossil Free initiative organized by 350.org, a grassroots environmental organization based in Oakland, California and set up by writer Bill McKibben. He is the driving force behind the project, which urges investors to ‘freeze any new investment in fossil fuel companies, and divest from direct ownership and any co-mingled funds that include fossil fuel public equities and corporate bonds within five years’.

One of the organization’s senior analysts, Brett Fleishman, says 23 cities, nine universities and a host of churches have already divested or are in the process of doing so, along with 17 foundations worth a combined $1.7 bn.

Despite its origins, Fleishman says the success the campaign has enjoyed is because the decision to divest is starting to make financial sense. ‘If the companies in question are overvalued, how much will the beneficiaries lose when this bubble pops?’ he asks, naming HSBC, Standard & Poor’s and Deutsche Bank among those considering stranded fossil fuel assets a very real problem.

There are clear moral issues, too, for public institutions with environmental programs or values that invest in fossil fuels. ‘Divestment is a win-win,’ he continues. ‘Investors are minimizing investment risk while upholding institutional values.’

Activism and shareholder engagement aren’t as appropriate for 350.org’s aims, adds Fleishman, despite the success of some campaigns through shareholder resolutions and negotiations. Because the Fossil Free movement is targeting fuel companies’ core businesses, there is little a resolution could help with, he explains, while an ever-shortening time limit means years of negotiations could be pointless. ‘We are not looking to change companies; rather, we are working to support the transition to a more sustainable energy economy,’ he explains.

Engagement agenda

One area that has seen significant divestment for financial reasons is the coal industry. While coal remains the world’s most popular fuel for generating electricity, the share prices of pure play coal producers have fallen dramatically on the back of oversupply, growing alternatives – such as US shale gas – and worries concerning the sector’s long-term prospects amid government action to reduce carbon emissions.

Indeed, coal is the best example of how expected action over climate change is rewriting the financial outlook for certain sectors. HSBC released a report at the beginning of this year that said, given the potential for a ‘carbon budget’ that would limit how much carbon could be produced, coal assets could see their values cut in half. ‘It is fair to say the long-run future of coal is now ‘in play’ in commodity and equity research markets,’ the bank noted.

Craig Mackenzie, head of sustainability at Scottish Widows Investment Partnership (SWIP), which manages roughly £50 bn ($83 bn) in equity assets, says the plight of coal shows large-scale divestment will happen for financial reasons only. ‘None of the investors that have divested have done so on ethical grounds, or hardly any of them,’ he says. ‘They’ve all done so because they think prospects for the sector are looking pretty grim at the moment – and, arguably, that is the right way to do divestment.’

Mackenzie sees clear differences between the move away from coal and divestment campaigns targeting fossil fuel companies in general, pointing out that it’s much easier for investors to divest from the relatively small size and number of straight coal companies. ‘It’s actually very easy for investors to decide on ethical grounds to divest because that’s going to have no impact on portfolio performance,’ he says. ‘But that is very, very different from oil: in the UK, [oil accounts] for something like 17 percent of the FTSE 100.’

Larger institutions are usually barred from divesting on ethical grounds if it harms financial performance, Mackenzie adds. ‘We might see a few foundations do it if they’ve got the fiduciary discretion to divest but... I think the impact of the divestment campaign on oil and gas will be much more limited,’ he says.

SWIP now has almost no exposure to pure coal companies, but it does retain large holdings in the integrated mining companies. ‘They basically have a portfolio of commodities and they have strategic choices to make about where to invest,’ Mackenzie says. ‘We’ve been supportive of companies as they’ve gone through that process and encouraged them to control costs and be disciplined in their use of capital. By and large, they’ve been very responsive and now the question we’re asking the most is, Are you investing any new capex in developing coal?’

Carbon risk

Mackenzie views engagement as the route forward with most fossil fuel companies. In this spirit, he was part of a group of 70 investors that wrote to 45 of the leading oil and gas, coal and electrical power companies last year asking them to assess how changes in fossil fuel demand could potentially affect their businesses.

The letters followed a report in April 2013 by Carbon Tracker, a research project, and the Grantham Research Institute that said companies were developing fossil fuel reserves they would not be able to burn if governments acted to stop global warming from rising by two degrees – considered a dangerous level where catastrophic impacts become likely. In a victory for campaigners, ExxonMobil agreed in March to publish information on the financial impact of stricter carbon controls, the New York Times reported. In exchange, wealth management firm Arjuna Capital and As You Sow, an advocacy group, agreed to withdraw a resolution against the US’ largest oil and gas producer.

The rate of return oil companies are getting for their investment has been a concern among energy investors for some time, so raising questions about carbon asset risk and future rates of return has been very timely. ‘Unlike a lot of ESG engagement, this agenda speaks to core strategic issues for a very big sector, and really does plug into a pre-existing debate between mainstream shareholders and oil companies about the rate of capex and their disappointing returns,’ says Mackenzie. ‘We’ve had meetings with some CEOs and we’ve got a few more in the diary, and meetings with top economists at oil companies about their projections for demand. And I think companies have been pretty responsive; pretty much all the oil majors have announced reductions in their capex plans for the future.’

While investors are focusing much of their attention on carbon risk, water scarcity is another area of growing concern, notes Lubber. ‘Investors are also expressing concern about water scarcity and water use, which is directly related to climate change,’ she says. ‘In fact, several investors have already worked with Ceres to develop the Aqua Gauge, a new system that allows companies and investors to assess and address water risk in global operations.’

The second installment of the IPCC’s fifth report into global warming, released on March 31, offered its most comprehensive study yet of the impact of climate change. A synthesis report, tying together the research of working groups I, II and III, is due out in October. Investors expect the research to spur more government action, which will, in turn, affect their own next steps.

For long-standing advocates of action to curb climate change, like Smith, the added urgency of investors and policy makers is welcome, although it may not go far enough. ‘The problem of course on the climate issue is that the clock is ticking, and it’s ticking rather dramatically – and therefore we need to move much further, much faster,’ he concludes.

|

Climate chat |

|

Engagement approach |