There are shades of the hare and the tortoise in the great sustainability race

Move over, Europe. You took an early lead in all things environmental, social and governance (ESG). Now you’re about to be one-upped by the same bloated capitalist machine that used to ignore your good deeds: here comes the US, still driven by greed, but now greedy for the profits that come from improved ESG.

European companies such as Nokia and Novartis have long been held up as models of ESG best practice, as reflected in Newsweek’s 2010 Green Rankings, which in October added a Global 100 alongside a US 500 first launched the previous year. Newsweek’s list, compiled by MSCI ESG Research, Trucost and CorporateRegister.com, has emerged as trustworthy amid a sea of sustainability rankings with credibility problems.

Out of the top 20 on the global list, 10 are from Europe with another six from tech-heavy Japan. Just four are from the US (including the top three – IBM, HP and Johnson & Johnson). But those few are the tip of a green American iceberg, according to Cary Krosinsky from Trucost. ‘A lot of European companies have taken the lead, but maybe not as many as people think,’ he says. ‘Now US companies are leading the way, taking more initiative and making big plans.’

That goes counter to popular opinion given America’s scant environmental regulation, its absence at December’s Cancun climate summit and its overall gas-guzzling image. For the Newsweek rankings, Trucost talked to hundreds of US companies, not just the few dozen from among the world’s largest 100. The conversations showed they’re taking seriously the strategic risks and competitive issues around sustainability. ‘There’s a litany of reputational, customer, employee and brand issues that are becoming increasingly important,’ Krosinsky says. By contrast, in Europe, outside of the big ESG pioneers, smaller companies aren’t changing as fast as they are in the US.

CRD Analytics, which recently expanded the NASDAQ OMX CRD Global Sustainability 50 Index to 100 companies and signed on to provide ESG analysis of all NASDAQ companies, uses its SmartView platform to produce a Global 1000 ranking for Justmeans.com. Michael Muyot, CRD’s president and founder, says many of the best performers are small and mid-cap companies in technology or life sciences. ‘And no one does that better than the US,’ he notes. ‘Much of the supply chain is all over the world but, in terms of innovation and solutions, it’s really in the US.’

A lot of the push toward change is from customers, whether it’s the government putting ESG criteria into requests for proposal, or Wal-Mart insisting on sustainability chops from suppliers. Employees are adding more impetus by wanting to work for companies that are environmentally and socially responsible. ‘The greening of the supply chain is one of the biggest business factors,’ Muyot says.

Finally, investors are demanding better ESG – at least they ought to be. In a recent survey of CEOs by Accenture in partnership with the UN Global Compact, CEOs say they care about sustainability but complain that mainstream investors don’t. Only 22 percent of CEOs believe investors will be key to driving sustainability over the next five years. And despite the huge success of the UN’s Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI), which has 830 signatories from 45 countries with more than $25 tn under management, mainstream investors haven’t really twigged yet.

Change on the horizon

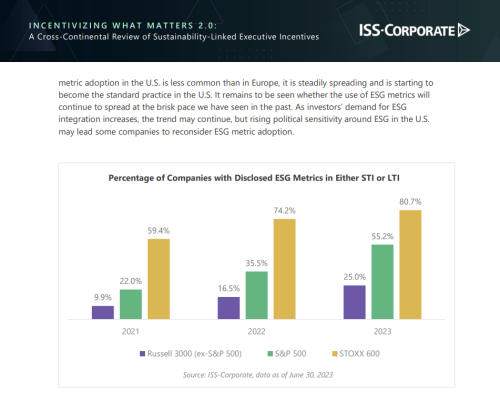

Krosinsky estimates that for European companies, especially large caps, 50 percent to 60 percent of their shareholder base has an ESG angle. In the US it’s only about 15 percent. That may be about to change suddenly and dramatically.

The real push will come not from any altruistic desire, but from the promise of outsized returns. The evidence has been mounting that investments using positive ESG strategies outperform. In Newsweek’s US 500 ranking, for example, the 100 top-scoring companies outperformed the S&P 500 over the last year by 6.4 percent, and Mark Fulton, Deutsche Bank’s head of climate change research, has shown that climate change-specific investment strategies have outperformed benchmarks since the March 2009 market bottom.

That’s a strong argument for actively managing for ESG. Expect US fund management firms to jump at the opportunity, especially second and third-tier institutions: a $10 bn firm could easily double in size by adding green strategies.

And the money is already moving. MSCI, the equity index provider, acquired RiskMetrics in June 2010 after RiskMetrics had itself bought Innovest and KLD Research & Analytics in 2009. Now MSCI has some of world’s smartest minds in ESG analysis. It recently relaunched KLD’s green-focused indices under the MSCI name, and has argued that ESG criteria should be considered alongside financial metrics. In effect, MSCI’s acquisition of RiskMetrics flipped trillions of dollars of mainstream investment into the ESG sphere. ‘Looking at environmental and social risk is in the DNA of European institutional investors. The numbers in the US are going to dwarf Europe when ESG is layered onto current portfolios,’ Muyot says.

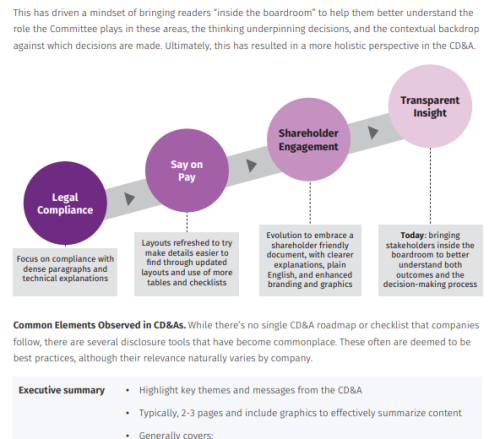

In Accenture’s CEO survey, variations in how companies communicate environmental and social messages to investors aren’t apparent between the US and Europe, but they are between developed and emerging markets. Around 45 percent of European and North American CEOs say they incorporate sustainability into discussions with financial analysts compared with more than 55 percent in Africa, Asia and Latin America. But neither number is as high as it should be, says David Abood, Accenture’s managing director of sustainability services in North America.

‘There’s a perception globally that financial analysts aren’t interested in sustainability. Our contention is that it’s not a lack of interest but a lack of understanding of how sustainability is driving business,’ Abood says. ‘It’s the CEO’s job to connect the dots.’ Of course, if that’s the CEO’s job, it’s the IRO’s job, too.

Unilever does it

The challenge for any company is how to weave together environmental, social and governance (ESG) measures with financial ones. Unilever’s new Sustainable Living Plan, unveiled in November, promises to halve the environmental impact of its products while doubling sales by 2020. In one stroke, Unilever has made its growth message and its sustainability credo one and the same.

Roger Seabrook, vice president of investor relations, is responsible for incorporating sustainability into Unilever’s IR. This global consumer products giant has long taken sustainability seriously. ‘But in recent years it’s moved from an issue of our responsibility to society – the good we ought to do – to a core part of our business strategy,’ Seabrook says. ‘That’s why it fits so well into our IR work.’

Unilever already produces a sustainability report separate from its annual report. Now it is setting hard targets under its Sustainable Living Plan and will be reporting on its progress on a special website (www.sustainable-living.unilever.com) and in dedicated reports. Seabrook sets out the business case as follows.

- Consumer preference: If there are two products on the shelf with the same performance but one has environmental credentials, that’s the one consumers are starting to prefer.

- Customers: Big retailers have made big sustainability commitments, so Unilever has to as well to get on the shelf in the first place.

- Innovation: ‘When you have these kinds of external challenges, that’s often when people are at their best in coming up with new ideas,’ Seabrook says. ‘This focus on reducing our energy, our water, our packaging should give us fertile ground to come up with new ideas.’

- Developing and emerging markets: Just over 50 percent of Unilever’s sales come from these markets, and they have the most immediate constraints in areas like water. To keep growing, Unilever has to confront those problems.

- Cost benefits: Unilever has already saved money on energy, packaging or distribution by, for example, concentrating products. ‘A lot of these initiatives ultimately generate cost benefits,’ Seabrook says.