Ian Cooke of AIB Investment Managers on being a US fund manager in Dublin, what he looks for in IR, and how he chooses his investments

You’ve covered US equities for 27 years. What’s changed in that time?

The evolution of the hedge fund industry, which affects the way stocks trade; it is now more volatile. Also, the way in which people evaluate companies has changed. When I first started, price-to-book value and dividend cover were much more important. Now it’s earnings growth, change in earnings (acceleration and deceleration) and sequential growth that really matter.

What’s different about being a US fund manager in Dublin rather than in London?

The one major difference I have found is that in London there is far more intense pressure on delivery of performance. This isn’t to say there isn’t pressure here in Dublin, but I found the London market more index-orientated. We have more discretion in terms of the risk structure, so there is much more flexibility in how we run our money here.

You’re not an index hugger then?

Absolutely not. My colleague Keith Johnston has over 20 years’ experience, as do I, in running US money, and we have top-quartile Lipper performance over one, two, three, four and five years for the region. This shows we have a very strong capability in being able to run US assets.

We have been delivering consistently over time without hugging the index. We invest in thematic ideas to play to our teams’ strengths. We identify stocks using fundamental research and our experience, which we believe enhances our performance.

What is your average holding period?

It varies, but the typical holding period would be at least 12 months. Some holdings we have had for a very long time. It’s very unlikely we would buy and sell something within one quarter unless there was a fundamental reason.

The sell criteria would be valuation, change in management, semi-fraudulent activity or change in market conditions. Market conditions could also determine whether we would either increase or lower the beta of the portfolio.

What are your size constraints?

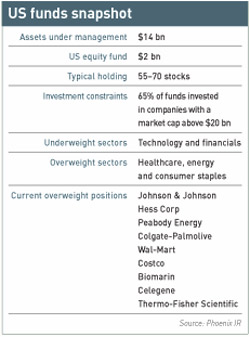

Typically we have a $2 bn market cap cut-off point. Occasionally, we’ll buy into $1.5 bn companies.

What’s the average size of a position?

It depends on how much we like the stock in question. We could be up to 4 percent over index weight if we felt a very strong sense of commitment to a company. We typically run somewhere between 55 and 70 stocks, depending upon our conviction in the market conditions at the time.

Which are your current largest US holdings?

We have a few 2 percent overweight positions: Johnson & Johnson, Hess Corp, Peabody Energy and Colgate-Palmolive.

We don’t have any big positions – 4 percent over index weight – at the moment. Wal-Mart and Costco are more than 2 percent holdings and Biomarin Pharmaceutical, Celgene and Thermo Fisher Scientific are all more than 1.5 percent holdings.

In which sectors are you currently underweight or overweight?

We are underweight in the technology and financials sectors and overweight in healthcare, energy and consumer staples.

Do you screen stocks?

Apart from all the necessary fundamental analysis of stocks, we do some screening. We might look for stocks that fit certain investment themes, such as coal and Peabody Energy. We might have met a company on a trip and it might be the right time in terms of valuation and earnings criteria to buy. With regard to the Yield Focus Fund you also have to look at dividend cover because dividends can get cut, as we have seen recently.

Do you have any investment constraints, such as no more than a certain percentage in certain sectors, or any market cap restrictions?

The constraints are that we can be 10 percent positive or 10 percent negative, which is actually quite a punchy bet and is what our investors and consultants like to see. For example, we have been significantly underweight in the financial sector, as we clearly saw where the risks lay within the market.

Do you see fewer companies in Dublin than you used to see in London?

Even in the short time I’ve been at AIB, the number of US companies visiting Dublin has increased. There are a lot of investment companies here: Pioneer, Banca Fideuram, Eagle Star, PI Investment Management, AGF, Bank of Ireland, and so on. We are not generally seeing funds being indexed over here the way they are in London.

Companies are now much more willing to come over to Dublin. We also do quite a lot of trips to the US: I typically go on three or four trips a year, so companies know who we are and where we are. A lot of US firms also have very strong Irish links, and Dublin is really on the map now so I would estimate we see possibly between 60 and 70 companies a year in Dublin.

Does meeting management make a significant difference to your decisions?

Absolutely, but I prefer to see senior management; it’s always worthwhile to see the CEO, CFO or COO. Top-notch IR people are good if they’ve been in that role for a while, but not if they’ve only been in the business for six months.

Who’s good at IR?

Apache and Cameron. Over the years, companies’ IR has improved significantly. Most of the energy companies have IROs who are switched on – people you can trust. This business comes down to trust: you’ve got to be able to look these individuals in the eye and see that their story is believable.

Who’s bad at IR?

I think a lot of financial companies tend to be poor. They don’t tell you the real story. They might blame difficult times, but they don’t always tell you the truth.

Who would you like to see visiting Dublin?

The likes of Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs – you don’t tend to see them here. IBM comes over, though I’m not sure Intel or AT&T does. Johnson & Johnson and Baxter don’t come here, nor do the major energy companies or the large-cap healthcare groups.

The one thing I noticed last week on my trip to the US is that a lot of US companies want more European shareholders; they want to diversify their shareholder base. I think they’ve got a good story to tell and they just find they’ve got too many hedge funds in the US influencing their stock price. For example, Celgene is actively looking for European shareholders. There is definitely an opportunity for US companies to diversify their shareholder base in Europe.