Investor engagement as important as regulation when it comes to improving governance practices in Asia

I recently had the opportunity to have dinner with Andrew Fastow, former CFO of Enron. We were speaking on a panel together at the ‘Financials hidden in plain sight’ conference led by Corporate Governance Board Asia and Straits Interactive and supported by the Malaysian Institute of Accountants, Boardroom, the Malaysian Directors Academy and the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants in Kuala Lumpur.

You may recall Enron, the darling of the US energy industry that during its heights had a market cap exceeding $60 bn. It left behind a human cost that still has shocks today, with 29,000 people seeing their jobs and medical insurance vanish. Investors lost $1.2 bn in pension funds and retirees lost just over $2 bn, all while Enron’s top executives reportedly paid themselves $55 mn in bonuses.

Fastow was CFO from 1998 to 2001. In 2004 he pleaded guilty to two counts of securities fraud and was sentenced to six years in prison. Since completing his sentence in 2011, he consults with directors, attorneys and investment funds on how best to avoid critical finance, accounting, compensation and cultural issues.

Avoiding another Enron

Unfortunately, despite today’s more regulated and enlightened business environment, we continue to witness Enron-style failures of corporate governance. Fastow observed that the frequent ambiguity and complexity of laws and regulations breed opportunities for loopholes and problematic decisions.

Corporate directors, management, attorneys and auditors should all ask the hard questions in order to ensure companies not only follow the rules, but also uphold the principles behind them; paradoxically, Enron’s mantra was: ‘Ask why’.

Fastow advised the audience to follow three practices at their companies: avoid aggressive accounting practices and use of loopholes, assess cultural risks and align incentives to sustainability. While nothing he shared is new, the reality is that few companies have successfully managed to address all of these issues on a global scale.

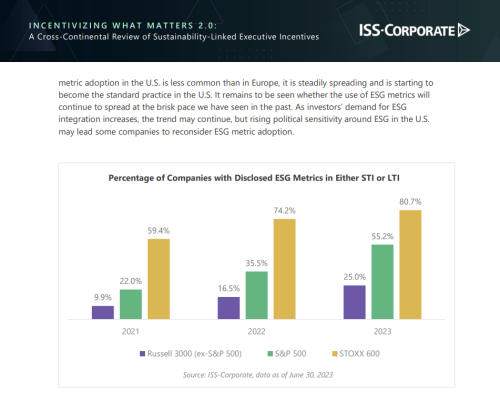

On the investor side, data providers such as Bloomberg, MSCI Ratings, RepRisk and Sustainalytics already assess listed companies’ ESG performance and feed the relevant data straight into their financial terminals. In addition, almost all firms receive copies of this information from their corporate secretary, chief risk officer or head of CSR.

But has anything changed since Enron? Looking around, we see many companies with Enron-like characteristics. If we take ‘aggressive accounting’ as an example, a recent review of portfolios across the five largest Asian markets shows a sizable share of companies displaying this practice, according to GMI Ratings and MSCI ESG research. While it’s easy enough for a responsible investor to exclude these firms from an investment portfolio, unless the investor engages with the firm and communicates publicly the reasons why it is not investing, little will change.

Similarly, when it comes to the tone at the top, there are still many listed firms in Asia that show poor corporate governance, have senior management teams with conflicts of interest and no independent directors on their boards.

From what you do to who you are

We are bombarded today on an almost daily basis with examples of companies or their executives who have taken shortcuts to an improved bottom line. As these situations turn out disastrously, the public outcry gets louder and regulators step in to ensure both the directors and senior leaders are held accountable for their actions.

Regulation is clearly not the only answer to the problem, however. With the rapid pace of business model transformation, digital disruption and new technologies emerging, coupled with the interconnectedness of risks, this will only result in there being more complex rules, an untenable level of compliance overheads – and even more loopholes.

Back in 2001, at Enron’s peak, reputation was based on what you do: as long as your economic performance, products, services and innovation road map were on track, you would be rewarded by investor advocacy and support.

With the advent of social media, companies have moved beyond the management of shareholders to the management of stakeholders. This is an important change that aligns with the latest RepTrak research, which illustrates that stakeholders are no longer only concerned about what you do but rather with who you are. Today, leadership, governance and how you treat your employees are dominant reputation-drivers. This is coupled with the clear fact that it is no longer acceptable to simply follow the rules.

The Leads checklist

Mike Love, former communications director of BT, Microsoft and McDonald’s, recommended in his recent presentation at UCL that all executives should know their Leads and ask themselves:

• Is it Legal? – both locally and internationally

• Is it Ethical? – is it regarded as unethical behavior by stakeholders even if it is legal?

• Is it Acceptable? – is it criticized by some, but regarded as acceptable by most?

• Is it Defensible? – could we defend our actions if this became front-page news?

• Is it Sensible? – even if it fulfills all or some of the criteria, does it still make good business sense?

As a start, I suggest we all adopt Enron’s old catch-cry ‘ask why’ and take Love’s advice to apply our Leads.

Leesa Soulodre is managing partner and chief reputation risk officer at RL Expert Group